[00:00:08] Speaker A: Good planets are hard to find out. Temperate zones and tropic climbs and run through currents and thriving seas, winds blowing through freezing trees, strong ozone and safe sunshine.

Good planets are hard to find.

[00:00:35] Speaker B: Hello, case good listeners. It's every other Sunday again, and you're listening to sustainability now, a bi weekly case good radio show focused on environment, sustainability and social justice in the Monterey Bay region, California and the world. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschitz. My guest today is Kevin Bell, co founder and co director of the Sustainable Systems Research foundation in Santa Cruz, which is, not coincidentally, also the underwriter for this program. It is the underwriter for this program. He holds an MPA from the Kennedy School at Harvard University and has over 35 years of deep experience in the areas of low income advocacy, energy efficiency program design, education, and sustainable infrastructure in the public, private, entrepreneurial, academic, and nonprofit sectors.

You probably receive an electric bill from your local utility, but have you ever bothered to read it? Most people look at what they owe, complain bitterly about the cost, and pay the piper. How many listeners know what you actually pay for electricity? How much of your bill is actually the cost of generation, and how much is other stuff? And what is that other stuff? Why does California have among the highest electricity rates in the United States besides Hawaii? And why do those rates keep rising? And what is this fixed cost fee that the California Public Utilities Commission just approved? Will it really reduce the cost of electricity or lower your bill? Today on sustainability now Kevin and I are going to conduct a talmudic exegesis on reading and interpreting your electricity bill. For those of you in the know, the Talmud is the foundational rabbinic law in Judaism, consisting of reading interpretations and commandments derived from the Torah and endless discussions among learned rabbis. Your electricity bill is a much simpler document. But the reasons for what and why it includes certain charges, are somewhat more obscure and opaque, and perhaps deserve a closer reading. We're going to use a pg and e bill as our text. Today, most electricity bills include the same elements, if not in identical. Order. To help you follow, we have created a PDF document online.

As we proceed through this exercise. You can find

[email protected] three k s six. Just to repeat that, tinyurl.com three ks six j ust or you can follow with a copy of your own bill.

Kevin, welcome to sustainability now.

[00:03:15] Speaker C: Hi, good to be here.

[00:03:16] Speaker B: I seem to recall that many years ago, electricity bills were simpler things. Here's how much you used. Here's how much you owe us. Why are today's electricity bills so complicated?

[00:03:26] Speaker C: There is a long and tortured history to what has happened with electrical energy in the United States over the last 50 years or so. Particularly, it's even more complicated in California than a lot of places. We could easily do a radio show just on how we got to that. But the short version is that the electrical energy grid and the politics of electrical energy in California are dominated by three large privately owned utilities. Pacific Gas and Electric, southern California Edison, and San Diego gas and electric. PG and E is the one that we care about locally. The reasons for those utilities to exist has been questionable for at least 40 years. Those utilities make a lot of money maintaining control of the grid, and they have gone to extraordinary lengths, along with the Compliant Regulatory Commission, California Public Service Commission, and legislature, and unfortunately, some major environmental consumer organizations, like, naturally, defense council, to maintain control. And so what you're looking at is basically 40 years of accumulated band aids that have been attached to what was initially a fairly simple electrical energy bill to prop up those utilities and to prop up that control, and to prop up a vision of California's energy feature that is basically, at this point, on track to fix.

[00:04:53] Speaker B: There are two charges on the bill. One from PG and E, the other from Central coast community electricity, also known as three CE. Why are there these two distinct charges? What's the difference between the two?

[00:05:05] Speaker C: The extreme short version is that the Central coast community energy handles your actual energy, the actual kilowatt hours that flow to your house. What happened was, up until, actually, up until 2002, the model was that you have a centralized kind of hierarchical utility that builds huge power plants. They deliver electricity over big transmission lines to smaller and smaller systems, down to the distribution line that runs down your street, and that everything all the way down was controlled by PG and E. In the nineties, it became pretty clear that you didn't really need centrally controlled utilities for any part of those three main functions. Generation, transmission, distribution. And the part that came apart first was generation. And most of the generation in California, and actually the United States is no longer controlled by big vertically integrated utilities. California's attempt to kind of restructure the industry was a catastrophic failure. It resulted in driving prices up to dollars per kilowatt hour in California. Over the winter of 2000. 2001 nearly blew up the economy of the entire west coast. And pg and e went bankrupt. They should have stayed bankrupt, but the state went to extraordinary efforts to bring them out of bankruptcy, throwing more money at the problem. Consumers were upset enough that the legislature passed a law in 2002 that allowed local communities to develop their own energy portfolio. That was separate from Pacific gas and electricity. And the one here is the Central coast community energy, called community choice aggregator, or CCA, that handles electricity from San Luis Obispo county to Santa Cruz county, based on the entire central coast. The utilities hated it. They spent ten years trying to prevent them from forming. The first one was formed in Marin county in 2012. Once the utilities lost in port unit choice aggregators sprung up all over the state. Consumers basically abandoned the energy portfolio for those electric utilities. And in the case of Central coast community energy, they came up with an energy portfolio that is much closer to zero. Carbon does not include nuclear power, although that change in politics and costs less than half of what the energy portfolio from pg and e costs. And so when you're looking at the ratio here, what's important is that up until about 1990 or so, about half of what was on your utility bill was energy and the other half was transmission distribution. If you look at your bill here, you'll see that the actual energy part of this is a third, not a half. And as we dig into this, you'll see the actual energy charge is an even smaller fraction of what you're actually paying for on your bill.

[00:08:03] Speaker B: Well, we'll come back to that. PG and e is a private investor owned utility. Three CE is a public, nonprofit joint powers authority. Three CE distributes electricity to its customers. Right. PG and E basically moves electricity from the generator through the transmission grid and then the local distribution system. Now, how do they each generate their revenue?

[00:08:28] Speaker C: Okay, it's a little more complicated than that because there's a lot of independent generators. The only way that you can not have the utility that owns parts of the transmission system gain their ownership of the transmission system is to have an independent authority that actually handles the transmission transactions. And in the case of California, that's the California independent system operator. It is unfortunately not controlled by the state. It is controlled by the investor utilities. There's chunks of the transmission system that are owned by public utilities. They are not part of that grid operator because their system is so much cheaper. It's not to their advantage to join the grid operator, but basically because Pacific gas and electric still owns chunks of the state transmission system and because that was paid for by private investors instead of by a public utility like La Department of Water and Power Sacramento, they are guaranteed a return on investment that is large relative to the risk they're taking for their control pieces of the transmission system and your local distribution system. And so we're going to get into the energy part of this in a minute. But they make money by convincing the Public Utilities Commission to give them a 10% return on investment, guaranteed return on investment, on whatever they can convince the Public Utilities Commission to spend money building new transmission, rebuilding transmission stuff that got burned down in fires. Building distribution system, rebuilding the transmission system when it falls apart because they haven't been maintaining it. And then all of the charges that have been added to keep the utility afloat after two bankruptcies. Basically the only thing that the community choice aggregator is doing right now is finding cheap power. They pay actually extra on top of what you pay on your bill for transmission to PG and e to make that energy available to you. So central cost, community energy is handling energy, piece of this. And PG and E is getting paid basically to handle everything else. Plus make sure that the investors are still making money, even though there have been a lot of mistakes over the last 30 years.

[00:10:45] Speaker B: Okay, for the purposes of this tutorial, we're using one of my electric and gas bills from PG and E. There's six pages to a pg and e electricity bill. At least to my bill. There may be longer for other people. The first one shows how much you owe. The second page includes a variety of definitions, but not everything that's on the bill. And it's not until we get to the third and fourth pages that we find details of electric delivery charges. This third page shows PG and E's charges, the four, three ces. Let's begin with the PG and e page. Can you explain the following? Why are there two different rate schedules from PG and E?

[00:11:29] Speaker C: You're getting two because if you look at the billing period on this, it's from the third week of February to the third week of March. And rather than just tell you what happened between 30 to February and third week of March, they have to break it out by month. And so the top part of it, this is true for my bill as well. The top part is one week of the previous month, and the second one is for three weeks of the current month. As you can see in this bill, the actual charges, month to month change basically from the last week of February to the first week of March. Basically, it's a. It's an artifact, because they are tracking stuff by the month, but they're billing you by something that is third week to third week.

[00:12:15] Speaker B: Another thing on this document is to terms peak and off peak. And the charge, at least from PG and E, differs marginally between peak and off peak. What does that mean?

[00:12:27] Speaker C: Basically what we're looking at is there's basically two ways that you can get billed.

Some people, especially if you don't have solar, are going to basically pay a flat rate. So whatever time of day you're using stuff, it's a charge that is something between the peak and the off peak rate.

If you want to be able to charge your ev at night and not pay as much at night, if you have solar and you're selling power back to the utility, which turns out to not be a very good deal for you, then you are required to use what's called a time of use rate. What happens is basically at night not a lot of people are using electricity. In the morning, people get up, there's a little spike, and then throughout the day people are at work. But also throughout the day, because we have a lot of renewables now, there's an enormous amount of cheap solar power in the morning and mid afternoon. There's a crunch at the end of the afternoon and into the evening, especially in the summertime where everybody comes home, fires up the air conditioners. In the summer there's less solar. Wind power tends to come on in the evening, but there's usually a period of a few hours in the late afternoon and early evening where renewables have tapered off. You can fix that with storage, but we're still building our storage capacity and so they have to bring up a lot of gas power plants really quickly and those are expensive to run. So cost of providing power in that few hours is much higher. Basically, the PUC allows the utility to charge extra for transmission, distribution and energy in that peak period. And the idea is basically to try and give people an incentive to not use power on peak. There's a lot of reasons why it doesn't work like it's.

We'll just leave it at that. So what you're seeing here is basically peak and off peak charges reflect the difference in what the PUC allows PG and E to charge during the peak, late afternoon, early evening hours, and other times of day or other seasons.

[00:14:41] Speaker B: Just one note, as I recall, we were customers were offered the choice of staying on the flat rate for a certain amount of time or going to time of use rates.

But those with the flat rate I think were ultimately shifted to time of use rates as well.

[00:14:59] Speaker C: They havent been yet. And people are kicking and screaming about going to time of use rates because its really not a good deal for customers. But yes, the PUC is in the process of forcing everyone to use time of use rates, whether they want to.

[00:15:14] Speaker B: You're listening to sustainability now. I'm Ronnie Lipschitz. And I'm in the studio today with Kevin Bell, and we are doing a talmudic exegesis of a PG and e electric bill. If you want to follow along, you can find a

[email protected].

three ks, six j ust. Or you can follow with a copy of your own bill. We've just been talking about PG and E's electric delivery charges. The difference between peak and off peak. One interesting thing, Kevin, is that the difference here, because this is transmission and distribution between peak and off peak is actually rather small, as we'll see from three c and e. The difference that three c and e charges for peak and off peak is quite a bit larger. But let's go on. There's a baseline here, which is for Santa Cruz, it's 7.5 kilowatt hours per day. And what does that mean?

[00:16:12] Speaker C: Part of the problem is that in rate making, there's a principle that you apply that basically it's cost based and that you don't discriminate. But California made the decision a long time ago to basically skew rates to reflect how you use electricity.

What they've established is there's 13 climate regions in the state, and then you are a high use electric customer because you have base 14, or heat pump or an EV. Or you are a low usage electrical customer because you have gas heat. So they have a complicated table that they go through every rate case where they say, if you are a Central Valley customer with electric baseboard heat and an air conditioner, we will give you more subsidized kilowatt hours than we will give you if you are a gas heat customer with no air conditioning in a milder climate like Santa Cruz. And so that baseline allowance is basically calibrated to whether you use a lot of electricity or not. It basically encourages you to use more electricity and whether you live in a regional that has, that's really hot or really cold. Another way to do this would be to focus on energy efficiency and best practices in those regions instead of giving you a break on your bill. But they chose to give people a break on their.

[00:17:42] Speaker B: The baseline varies also over time.

[00:17:45] Speaker C: That's right.

[00:17:45] Speaker B: It's not just regionally, it's for winter and summer.

[00:17:48] Speaker C: Yes. So it's winter and summer and region. Whether you're a high use or low use electrical customer, and because most people in Santa Cruz area don't use electricity, don't need air conditioning and have gas heat and are in a mild climate, our allocation is very low compared to, say, a central valley.

[00:18:08] Speaker B: Then the bill shows a baseline credit, which is some kind of reimbursement or reduction, price reduction for electricity use within the baseline.

[00:18:20] Speaker C: So if you look at your top, there's your baseline allowance.

[00:18:23] Speaker B: Right, okay. And then 52.5 kilowatt hours per week.

[00:18:28] Speaker C: So. Yeah, so seven and a half kilowatt hours a day. So what is that, about a little more than a quarter of a kilowatt, than 250 watts per hour? Quarter of a kilowatt per hour on average. So that's how much you get. And then the peak and off peak charges are. This is how much we would have charged you if we hadn't given you this break. And then below that you get a credit for the 52 and a half kilowatt hours that they're going to subsidize for.

[00:18:54] Speaker B: Now the next line shows a generation credit. What is that? I mean, I can explain it if you can't.

[00:19:01] Speaker C: If you can remind me what this is.

[00:19:02] Speaker B: Okay, well, the generation credit is a reimbursement for the generation charge at three CE charges me. Okay, so it's a deduction for the cost of electricity generation, which PG and E is not allowed to charge for. What's interesting, of course, they put it back somewhere else.

[00:19:21] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:19:21] Speaker B: So in this case it's.

[00:19:24] Speaker C: That's a credit for the baseline, for the baseline electricity that the CCA is providing.

[00:19:30] Speaker B: And then we have something called the power charge indifference adjustment, or PCIA. And I don't have any idea why one would be different to a power charge.

[00:19:41] Speaker C: Well, it's not you, it's PG and e shareholders that are indifferent. That's the intention. And it shows up in a couple of different places. What happened was that the community choice aggregators were coming in with energy portfolios that cost half of what the PGE portfolio costs. And part of why the PGE portfolio is so expensive is because they have Diablo Canyon, which was going to shut down, but they're going to keep it open. It costs between two and three times what the power from Munichoice aggregator costs. They have plants like moss landing, which cost much more than power from unit choice aggregator costs. The PuC wanted PG and e to move to solar. PG and E and the PUC do not want distributed or community solar. So they told PG and e to go out and get a bunch of bids for solar projects in the mid two thousands. And they let PG and e come in with whatever bids they wanted.

PUC did not really review what PG and E came in with, turned out that they came in with some long term contracts that were fixed price, incredibly expensive and are vastly overpriced compared to the market value of those resources like diabolican. And that the PG and E didn't build in any clauses where they could reduce the price from those contracts as the price of solar came down, which we knew was going to happen. So in order to guarantee the profit to shareholders, we're basically insulating those shareholders from any risk that the cost of power is going to get cheaper over time. PG and E is allowed to say, well, this is all the stuff that we're stuck with because you aren't buying energy from us. The energy in our portfolio is literally overpriced. It's so far above market that we won't make as much money. And so they are allowed to charge every community choice aggregation customer difference between what it costs for the CCA to deliver energy to you and what it would have cost PG and e to deliver energy to you if you were still getting power, PG and E. And it so happens that that charge happens to be the difference. In the case of some ccas, it means that CCA power plus that indifference charge, so that shareholders are indifferent, is makes that power from your local community choice aggregator more expensive. In the case of Central coast community energy, it makes the power barely less expensive. But the original reasoning going in for having community choice aggregators has been pretty much thrown out the window because the PUC is shielding PG and e shareholders from risk that they ticked on and did nothing to reduce over the last 20 years.

[00:22:53] Speaker B: So the PCIA is charged only to community choice aggregator customers? That's correct, because they've left PG and E and they are being made to pay for PG and E's poor business judgments and the PUC's orders back from the two thousands. Right.

[00:23:12] Speaker C: Insistence on protecting PG and E from the constant and southern California Edison SDG and e from the consequences of their actions.

[00:23:18] Speaker B: If PG and E had to charge and pay the cost of those contracts in Diablo Canyon, would it lose money? Do you have any idea?

[00:23:28] Speaker C: Oh, yes, they would absolutely lose money.

One of two things would happen. They would either go back to, they would shut down Diablo. First of all, Diablo is a white elephant. But they would go back to those overpriced contracts and basically say to them, look, we can't pay this, we're going to go bankrupt or we're going to renegotiate the contract. But this happens all the time in the real business world as opposed to the regulated utility world. And they would basically get a new contract or the utility would go bankrupt and we would have a system that is not controlled by PG and E.

[00:24:06] Speaker B: Let's go onto the three CE page, the community choice aggregator page. That's page three in the document, and this is the details of the CCA's generation charges. Now this is a much simpler page, but it is also in many ways more opaque. And one of the things you see here is that the peak and off peak charges from three c and e differ much more than the peak and off peak charges from PG and E. In fact, the on peak charge is about twice the off peak charge.

[00:24:40] Speaker C: Why is that so?

First of all, keep in mind that the average cost of the energy portfolio from civic coast community energy is about six cents. And then what youre seeing here is basically two things. One is that the mutual segregator has to pay this indifference adjustment. So thats reflected here. The other thing is that even though typically someone who's generating energy doesn't have to pay to get access to the transmission system or the distribution system, unless you're a distributed energy provider, the PCE has to pay extra transmission charges on top of what PG and e charges to get power from contracts in places like New Mexico to you over the grid. So you're getting transmission charges on top of the energy charges for unit choice aggregator pancaked on top of what they're charging. So that's part of what's going on here. And I cannot tell you what's going on for the rest of it, and neither can anyone else. I have actually gone to a fair amount of trouble to talk with experts I know in the industry and directly with Central coast community energy. And I have found no one who can explain to me where those charges, where those rates are coming.

[00:26:05] Speaker B: Someone suggested that it may be the cost of what's called resource adequacy.

[00:26:11] Speaker C: That is part of it.

[00:26:12] Speaker B: And what does resource adequacy mean?

[00:26:16] Speaker C: So the essence of being a utility, a regulated utility or public utility, is that you are able to provide energy to anybody who wants it when they want it. And the technical term is provider of last resort.

Traditionally, the investor and utilities, in return for making ridiculous profits, they are required to guarantee that anybody who wants to get electricity whenever they want. So in order to do that, they have to know that there's enough electricity there when people want it, they can give you that energy. And that's called resource adequacy. The community choice aggregators have the capacity to make sure that there is enough energy there when their customers want it. That is they are capable of providing that resource adequacy. However, over a period of several years, the community trust aggregators have gone back to the PUC over and over again and said, look, we have enough power. We have when people want it, we can do this. We can be the provider of last resort. And over and over again PUC has said, no, we're not going to let you do that. We insist that PG and e continue to be the provider of last resort and a source of resource adequacy. And whatever they want to charge you as the CCA for being that provider of last resort and that guarantee of resource adequacy, you're going to pay that. So to sum that up, the CCA is saying we can provide whatever people need and we can do it for cheaper. And the PUC is saying, we're not going to let you do that, and we're going to charge you whatever PG and E decides to charge you for that service.

[00:28:00] Speaker B: You're listening to sustainability now. I'm your host Ronnie Lipschitz, and I'm in the studio today with Kevin Bell, and we are taking apart an electricity bill from PG and E. In fact, it's one of my electricity bills, trying to explain what the different charges are and how they're calculated. And so far, if you've been following with the document that we prepared, which is

[email protected]. three ks, six g.

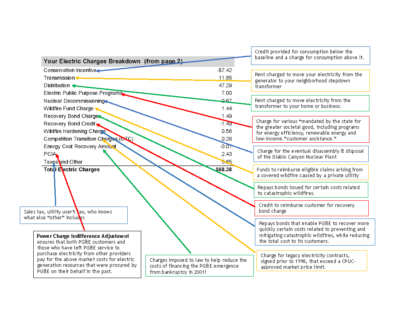

It's been pretty confusing. There are lots and lots of numbers here, and there's not a whole lot of explanation. We've covered the simple stuff, I think. And now let's turn to PG and E's electric charges breakdown. This is on page four of the document, and the breakdown consists of 13 rather poorly defined charges. You can find explanations if you go online, you can find definitions, not exactly.

[00:29:00] Speaker C: Right, although sometimes definitions are as confusing.

[00:29:03] Speaker B: As, and that is what makes up the utility's electric delivery charge. So we'll talk about that in, in a minute. What I noted, and what is interesting is that if you divide those charges by the number of kilowatt hours delivered or through the transmission system, PG E's average cost of electricity is about 29.5 cents per kilowatt hour, as opposed to the shown on page three. There are, of course, these various incentives that reduce the total bill, but I'm still not sure what accounts for the difference.

[00:29:40] Speaker C: And they wobble around a lot depending on they wobble around.

[00:29:45] Speaker B: Let's start with the conservation incentive.

[00:29:48] Speaker C: Basically back in the nineties, when energy conservation was still a priority, the commission decided to give you a break. If you were, if your usage was below the average usage of people in your climate zone electrical usage class.

And so if you're efficient relative to other users in the bin that you've been tossed in your climate, electric heat, air conditioning, whatever they space, the people use more than the average, pay a little extra, and that extra is flowed back to people that use less. And so what this is, is a reward for using less than an average user in your situation.

[00:30:42] Speaker B: I mean, it's funny because we didn't consume below the baseline. So I'm not quite sure where we.

[00:30:46] Speaker C: But you did consume less than the average user, the average non electric heat user in Santa Cruz.

[00:30:56] Speaker B: The next two items are transmission and distribution, and they make up the bulk of PG and E's charges on this particular bill, 86%.

So we've talked a little bit about TMD.

What's the difference between the two and how are costs calculated for the two?

[00:31:13] Speaker C: The short version is that if you're out and looking at these huge electrical lines coming from moss landing or running down Central Valley, those are transmission lines, and they're delivering power from huge hydropower dams, from nuclear plants like the canyon, from gas generators like moss landing and solar farms, and solar farms. They're moving basically power in the range of thousands of megawatts of power. If you think kilowatts 1000 kw is a megawatt, thousand megawatts is a gigawatt. California, on average, is moving on the order of 35 gigawatts of power on these huge high capacity transmission lines. They're bringing power from the west, from Arizona, moving it around California. So that's the transmission system. And then it steps down to a lower level. Technically, the transmission lines are moving about 500 power on those big power lines at a time. And you get down to the power line that's running to Santa Cruz, and it's about 100 mw or less. And so there's a point where they say, okay, as you get down to lower and lower power, you get down into the local system. That local system is what's called the distribution system. And that goes all the way down to the transformer that drops power from the street to your house. So basically, everything in your. Everything from the city, the entrance to the city of Santa Cruz down to your house is what's considered the distribution system.

[00:32:51] Speaker B: What I don't quite understand is why, if that single kilowatt hour is coming from very far away and then is being distributed, you know, from nearby transformer stations, why is the cost for transmission so much higher than the cost for distribution?

Yes. Transmission is $11, distribution is $47.

[00:33:15] Speaker C: So distribution is more expensive?

[00:33:17] Speaker B: Distribution is more expensive, yes.

[00:33:19] Speaker C: Basically, there's a couple things going on. One is that transmission system, that the transmission system overall is cheaper per kilowatt hour to maintain because you're moving so much more power and not very many wires. The distribution system is really complicated. It's a lot of wires, a lot of transformers, a lot of drops to your house. There's just more stuff there. And part of the problem with both the transmission distribution system, in the case of PG and E, is that the PUC gave them money to maintain those systems, but they don't make a profit on maintaining the systems. So they haven't maintained the systems and they're falling apart. That's part of why we have catastrophic fires. That's part of why the distribution system in Santa Cruz is terrible. And we get regular outages, UCSC campus, in our neighborhood. Basically, the powers are not that reliable, but it is expensive to maintain because it's complicated. And one of the things that is about to happen is that distribution system basically needs to be resorted from the ground up. One of the interesting things about this, of course, is that if you're producing energy locally, that energy is being passed around on the local distribution system. It never touches the transmission system. You are reducing traffic on the transmission system. There's a lot of talk now about spending a lot of money on new transmission corridors. If you have a lot of distributed local energy, you don't need as many big transmission investments going forward. But uniquely, instead of if I'm delivering power from a wind farm on a transmission system in New Mexico, I don't have to pay access to transmission system.

If I'm a customer on a distribution system that wants to put power into the distribution system, I am expected to pay power in and take power out. So both the transmission distribution numbers are about to go up. The distribution number is going to continue to be a lot more just because there's more stuff. It's a more complicated system to maintain.

[00:35:23] Speaker B: Okay, the next category is electric public purpose programs. And those are defined by the utility as a charge for various programs mandated by the state for the greater societal good, including programs for energy efficiency, renewable energy, and low income customer assistance. These sound like programs that ought to be funded through public funds, like taxes. Why are they on my electricity bill?

[00:35:54] Speaker C: Because in 1997, the state of California made a really incompetently executed decision to try and separate out the generation transmission distribution functions of the big three investor utilities.

Part of why the restructuring got screwed up was because the PUC and Natural Resource Defense Council lobbied the legislature successfully to have the terms of that restructuring be very favorable to the investor utilities. And a lot of these other charges we're going to see are related to that decision. The carrot that brought natural resources defense counsel along. And it is important to understand that absent the active support of Natural Resources Defense Council and catastrophic restructuring legislation in 1997 would not have happened. The carrot was that there was going to be a dedicated fee that would be set aside to basically force the electrical utilities to focus more on energy efficiency. And that's what the public programs were. How the utilities spend that money has not been regulated in practice. Most of that money has gone to make the compact fluorescent and led lights that you buy at Home Depot cheaper.

And part of why those are not very high quality lights is because they tried to save money by having the things that they're going to subsidize through the public purpose program be cheap. So it started out as a big deal. It was basically a bribe to get natural resources Defense Council to advocate for that catastrophic legislation.

History has kind of pass it by. The impact on efficiency, low income programs or anything else has been pretty much nothing. And it's still there.

[00:37:54] Speaker B: Next comes nuclear decommissioning. Why are we paying for decommissioning if Diablo Canyon is still operating?

[00:38:02] Speaker C: Because the theory, again, when the United States made the decision to try and do commercial nuclear power, it was a huge liability issue. Nobody would build these things because there was no way to pay for it if something went wrong. So the federal government basically provided subsidized insurance for the industry. And there was no guarantee that once these things were worn out, we would be able to take them apart. Basically, you've got this radioactive building and a bunch of radioactive fuel. And the time we had an idea what we were going to do with the fuel, we don't. So the idea was that we'll set up a fund, and every year for the 40 year life of the nuclear plant, we'll pay money into that fund. And at the end of it, when it's time to basically decommission the plant and take it apart, we'll have this fund to pay for it. As you can imagine, the estimates for what that was going to cost are ridiculously low. That fund is not going to pay for decommissioning the plant. Even officially at this moment. If we actually went ahead with decommissioning Diablo next year, like we're supposed to. That fund is a billion dollars short. But federal government and state government have thrown $2 billion in subsidies at keeping Diablo open. Kind of the fixes in to keep it open, even though it remains one of the most expensive energy sources in the state and is old. We don't know how much longer it's going to last. And it causes a lot of environmental damage. That's why they were going to close it. That's out the window now. Basically, that fund is going to continue to try and through enough money to be able to take the plant apart, encasing in concrete, keep it so it's no longer a hazard once the plant is. Finally.

[00:39:45] Speaker B: Have any nuclear power plants in this country been decommissioned that way?

[00:39:49] Speaker C: I know there are. Trojan power plant has been decommissioned. Santino has been decommissioned.

[00:39:53] Speaker B: Well, they're not operating anymore. The question is if they've been taken apart.

[00:39:57] Speaker C: They are in the process of being decommissioned. And the funds that were approved for that decommissioning have proven to be inadequate to actually decommission, yes.

[00:40:08] Speaker B: Okay. The next four charges have to do with wildfires and recovery bonds. And I've put them all together, but I'm wondering, what are those?

[00:40:19] Speaker C: So, because PD chose to reward their shareholders instead of maintaining the transmission system, there were portions of the main transmission corridor that PG and e built and controls where things like the hooks that hold the wires under the towers were 100 years old. And the wires had literally worn through the hooks and fell down and caused fires. Caused catastrophic fires in 2017 and since then. But in 2017, they burned through. They burned the city of paradise, which is half the size of Santa Cruz, to the ground, destroyed thousands of square miles of forest, killed 84 people. PG and e pled guilty to manslaughter charges and paid a fine of $41,000 per person. They killed and basically declared bankruptcy because they were liable for about $20 billion in debt. They should never have come out of bankruptcy. The story of how they managed to do that is something maybe we can cover in a different. In a future program. But the upshot of that is that the state provided a $12 billion subsidy to the utilities in order to. In fire insurance, basically, so they don't have to. They're no longer liable for any future wildfires. There was a fund to supposedly pay back fire victims. That fund is going to get liquidated this year. Fire victims are going to be lucky to get $0.50 on the dollar out of that fund. That's related to the coming back from bankruptcy. So we won't get into that. But basically, PG and E is allowed to charge about $9 billion to rebuild infrastructure that was destroyed in those fires. That's the recovery bonds. They are required to pay back the state for the $12 billion insurance subsidy. That's the wildfire fund charge. And they're being allowed to charge extra to do what they're calling wildfire hardening. And part of what's interesting about all of those things is that it's cheaper in a lot of rural areas to not have those areas connected to the grid, to basically have local distributed systems, but that's not as profitable. So PG and E would like to double down and rebuild the system that they had. Their solution is to, instead of having the transmission lines on towers, is to underground them, which is a lot more expensive, more profitable to the shareholders. But that's part of it. There's things they can do to cover above ground lines so there's less likely to fall down and start a fire. That's part of the wildfire hardening charge as well. So it's basically all charges that they're authorized to recover, covered to make their money back from the catastrophic fires that they cost in 2017.

[00:43:12] Speaker B: You're listening to sustainability now. I'm Ronnie Lipschitz, your host, and I'm here in the studio with Kevin Bell. And we have been deconstructing a PG and e electric bill and trying to explain what all of the many charges on the bill are for. We've gotten down, we're on page four of the handout, and the handout you can

[email protected]. three k, six, j ust. And we're now down to competition transition charges, actually, PCIA and energy cost recovery amount, all of which seem to have something to do with contracts and costs incurred by PG and e some 25 or more years ago. What is the competition transition charge?

[00:43:56] Speaker C: Okay, so just to, just to reiterate, so we have charges here that are from mistakes we made in developing nuclear power in California. We have charges that are related to a catastrophic attempt to restructure the industry in the late nineties, which led to the first bankruptcy of PG and E in 2001. And we also have a bunch of charges that are related to the second bankruptcy in 2017 that was related to their failure to maintain resources system. The competition transition charge dates back to the restructuring legislation from 1997. And it's basically the 1997 version of the indifference charge. At the time, PG and E said, look, we have all these contracts, and people are going to buy the power from somewhere else and we're going to get stuck holding these resources that cost more than the market price of power.

The commission imposed a competition transition charge that was basically equivalent of the power cost indifference adjustment from when they thought that they were going to separate PG and e out in the 1997 legislation. After the 2001 meltdown, they decided not to do that and decided to keep PG and E as a vertically integrated utility. But the conservation transition charge remained, and what it basically, it reflects another little shell game that was played at the time where utilities were selling regulated power plants like moss landing. Moss landing was sold to Duke Power, which is a utility from North Carolina. Duke Power had money to buy that because they were selling regulated power plants to somebody else. PG and e took the money from Moss landing and invested it in power plants in Massachusetts that used to be regulated, that weren't regulated anymore. So it was a way, basically, of taking stuff that was power plants that were being regulated and moving them out of the scope of being regulated by anyone. And the difference between what they made doing all that and what it costs them to implement the restructuring plan that failed is the competition.

[00:46:05] Speaker B: Well, we're starting to run short on time. Can you give us a sort of two minute summary of what the fixed cost charge, which is supposed to appear on utility bills, I think in 2026, what that's about?

[00:46:18] Speaker C: Yeah. So basically what PG and e wants is to not have to worry about their shareholders getting money no matter what. And they're worried because as people start to generate their own power, as what needs to happen is that local governments and power co ops and insurance aggregators need to step up because they can provide a full range of services for a lot cheaper than PG and E. So what PG and E would like is to move to a subscription plan instead of. One of the fundamentals of how you regulate has always been that you pay based on how much it costs to serve you. And what PG and e would rather do is go to an Amazon prime model where you pay them $25, $50, $100 just to be connected to the system, whether you use it or not. If you look at my bill from last month, I have an oversized solar system, I have an oversized storage system. I could be providing a lot of power to the grid, but I will be punished if I do so. I used two kilowatt hours last month, enough to run the meter. I paid dollar 20 a kilowatt hour for those 2 kw just to be on the system. What PG and E would like initially proposed, because I have solar on my roof was to charge me $100 a month whether I use any electricity or not. Then they came up with a plan to look at everybody's individual tax records. And charge them a subscription fee based on their income. Fortunately, that blew up because the tax franchise board came back and said, it's illegal for you to use information from. We know what people's income is because they pay taxes. It's illegal for you to have that information. And so after a huge rate case, they came up with a plan that basically said, well, people who are poor have already given up their right to privacy about what their income is. And so we'll set up one subscription fee for people that are poor. And one for moderate income people, where we have a way of getting access to how much they earn. And then everybody who we can't charge based on income, we're going to charge them another flat fee. And in this case, it's $24.50. It is going to go up. One of the interesting things about that is it's supposed to cover the fixed cost of transmission distribution charges. What are those charges? There's the cost of maintaining stuff, there's cost of building stuff. And then there's the fixed cost of just paying for the system, paying back everybody who invests in that system. We know what those charges are. Those charges are what's supposed to go into that subscription fee. And nobody that I've been able to talk to can begin to tell me where those exact charges are even documented. In fact, I don't think anyone, any individual person actually knows what's in that subscription charge. And over the next few years, you will see continuing efforts by the utilities. To increase that subscription charge. So they don't have to rely on whether or not you're using electricity to make them. And that's where that's coming from.

[00:49:23] Speaker B: Well, one last question, and make the answer short. Will we beat out Hawaii to become the most expensive electricity in the nation?

[00:49:31] Speaker C: Oh, yes, we're there. It is astonishing that California, that things have gotten so bad and so complicated that we are on the verge of overtaking Hawaii. Hawaii, interestingly enough, starting with Hawaii. But after the catastrophic fire in Maui, probably Maui Electric is going to go bankruptcy. Whether or not it's parent corporation has to go bankruptcy or not, we'll see. But the Hawaiian PUC has proven more responsive to the situation than California PUC. And I think we are going to see a situation where the private utility in Hawaii becomes less important and rates decline as the state starts to rely more on distributed energy networks and publicly controlled energy networks. California is on a path to basically continue with accelerating rates. So I think we're going to see California pass Hawaii within five years. This is important. If I have just a few more seconds. I have devoted a lot of my professional career working with the Washington Utilities Commission, Washington Energy office, as a low income advocate, as a consumer and environmental advocate, as a private consultant trying to prevent investor owned utilities from ripping off customers and the public. In California, we fail.

But the climate situation is so dire and our need to change quickly and efficiently to a system that doesn't kill the planet is so important and so urgent that if I have to throw overboard the idea that some people aren't going to make an obscene profit in that transition, I will do that. This is more important than that. It's not just these guys making a lot of money. California is on track for its transition to a low carbon electrical system to fail. And so it's not just that it's expensive, it's that the way that California is trying to make that transition is not going to work on the path. And that's the fundamental challenge.

[00:51:42] Speaker B: Well, Kevin Bell, thank you so much for helping to read and interpret electricity bills.

[00:51:47] Speaker C: Thank you so much for having me.

[00:51:50] Speaker B: I'm sure our listeners will have many questions about their own bills, and you can send your questions to me at rlipsch.edu and I'll endeavor to reply to them as soon as possible.

[00:52:04] Speaker C: And I'll endeavor to assist Athens.

[00:52:06] Speaker B: If you'd like to listen to previous shows, you can find

[email protected] sustainabilitynow Spotify, YouTube and Pocketcasts, among other podcast sites. So thanks for listening and thanks to all the staff and volunteers who make Ksquid your community radio station and keep it going. And so, until next, every other Sunday. Sustainability now.

[00:52:48] Speaker A: Into breathing trees strongholds on safe sunshine.

Good planets are hard to find. Yeah, good plan.