[00:00:08] Speaker A: Good planets are hard to find out Temperate zones and tropic climbs and run through currents and thriving seas Winds blowing through breathing trees and strong ozone and safe sunshine.

Good planets are hard to find. Yeah.

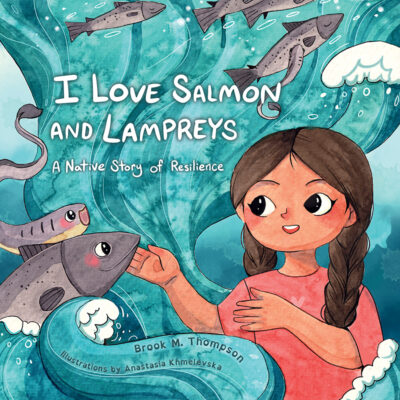

[00:00:35] Speaker B: Hello, K SQUID listeners. It's every other Sunday again and you're listening to Sustainability Now, a bi weekly case Good radio show focused on environment, sustainability and social justice in the Monterey Bay region, California and the world. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschutz. Until very recently, salmon and other fish attempting to spawn in Northern California's Klamath river found a number of dams in their way. Over the past several years. In the largest project of its kind to date, those dams have been removed. Now the watershed is being restored to let the salmon swim upriver and allow other plants and animals to return. My guest today is Brooke Thompson, a member of and restoration engineer for the Yurok tribe, PhD candidate in environmental studies at UC Santa Cruz and author of I Love Salmon and Lampreys, an illustrated book for children. She is the recipient of many awards for her work and art, as well as numerous scholarships. Her doctoral work is focused connecting water rights, Native American knowledge.

Her doctoral work is focused on connecting water rights and Native American knowledge through engineering, public policy and social action.

Brooke Thompson, welcome to Sustainability Now.

[00:01:53] Speaker C: Thank you for having me.

[00:01:55] Speaker B: Why don't we begin with some background first? Tell us something about yourself. You know, who you are, what you do.

[00:02:02] Speaker C: Yeah, a little bit about me is I'm from the Yurok and Koduk tribes in Northern California. I am currently a PhD student at UC Santa Cruz in environmental studies. But I also have a bachelor's in civil engineering from Portland State University with a minor in political science as well as a master's in environmental engineering with the focus on water resources and hydrology from Stanford University.

And I currently work part time as a restoration engineer. And I also just wrote a children's book. So I. Those are, I guess, just a few things about me and my last few years.

[00:02:45] Speaker B: Okay. Well, I read that that when you were seven, you saw a massive fish kill on the Klamath river. And that that had a really big effect on your sort of perspective and, and decisions about what to do with your life. Can you tell us something about that?

[00:03:01] Speaker C: Yeah. In 2002, I was seven years old and that is when I witnessed the largest fish kill in California history where I saw over 60,000 salmon die on the Klamath River.

And that was really a defining moment for me because these salmon's bodies were the same size of my own as a 7 year old. And the salmon were not only just a large food source for my family, a large way we made money. It's the only way I was able to afford school clothes growing up or school supplies. It was also the fact that these salmon had a very strong cultural and spiritual tie to me. The salmon that I saw dead and dying are salmon that are the great, great, great, great grandkids of the salmon that my direct grandparents knew.

And so my family has been taking care of the salmon since time immemorial, Meaning that these salmon have had a relationship with my family for thousands of years. And that I feel this connection to my ancestor and this intergenerational love that's passed down through the salmon that was destroyed within one day from poor decisions around water policy, decisions around withdrawals, with decisions around the dams in the Klamath river that my tribe didn't have a lot of say in. And yet we faced a lot of the repercussions of being downriver people. And that moment has stuck with me my entire life and has been one of the main reasons I became an engineer and became an author and am doing the research work I am now on salmon because of how devastating that was and wanting to make sure that does not happen again.

[00:05:05] Speaker B: But how did that influence your decision to pursue civil and environmental engineering so specifically, you know, specifically, as opposed to biology, let's say?

[00:05:16] Speaker C: Yeah, I mean, to think about it, one of the reasons I got into civil and environmental engineering. And at first, I think there might be a lot of people who don't even quite understand what that means. So civil engineering is, like any big structures, you do not want to move. So think about, like, roads, highways, buildings, bridges, and dams. And environmental engineering is the water component of that for me, mainly so understanding how water works. And so going into civil and environmental engineering, that was a way for me to understand how the dams that were affecting my river negatively actually worked. And giving a mathematic and engineering perspective, in addition to the tribal side, I knew would give me a lot more weight when having discussions around dam removal and also why certain infrastructure negatively impacts tribes. And that also came about because my dad was a carpenter growing up. So I got to see kind of like the physical side, the building side of the engineering side, post design. And I wanted to be the person on the other side of the table that then gets to design these things, because if you understand how they're built, you can better understand how to take them down. And that was my goal in being in engineering, is to kind of get that weight behind my name and what I'm saying, because as, like, indigenous peoples, we have a lot of understanding of what's going on on the river because we're the ones who've been observing it for thousands of years, and yet we are often not heard or we do not have the language to articulate exactly what we mean. And because of that, we're often, like, disregarded in conversations. And so I also knew that having a degree and having these letters behind my name, especially from, like, an engineering school like Stanford, that I would be listened to more. And that has been proven true.

[00:07:13] Speaker B: So as a restoration engineer, what do you do exactly? What does that exactly entail?

[00:07:20] Speaker C: So restoration engineer can mean, like, a lot of things. But what I and my team mainly get to do is work on redesigning streams and habitat to be more habitable for aquatic species like salmon. And so, for example, one of the projects I've gotten to work on is a project in Or California, where they've been doing restoration there for some of the largest coho salmon holdouts. And that entails, like, making streams and rivers that have been neglected or changed in a way that's been more harmful to, like, these young fish and putting, like, wood back in the streams or putting better gravel back in these stream beds and making them meander or, like, have different types of flow that would be more akin to what was there 100, 200 years ago versus all the destruction that's happened in the meantime that's made it, you know, have higher fatality rates for these young fish species. So I. I kind of like to think of it, like, if anyone's ever played, like, the Sims games or, like, have played a video game where to get a terraform and make little streams and plant little plants on the side. That's kind of like what I get to do, but, like, in a math sense. Uhhuh.

[00:08:36] Speaker B: Huh. I mean, it's interesting that, that you're intervening in the environment.

Even though you're trying to restore the river back to some semblance of what it was a couple of centuries ago, you're still trying to reshape it, humans trying to reshape it. That seems perfectly fine to me. But I'm just thinking now about the contradiction in that, that we want to leave nature alone, but we have to intervene if we want to restore it.

[00:09:07] Speaker C: Oh, well, I mean, I think that I don't want to leave nature alone. I mean, okay. I think that's one of the kind of fallacies that's happened over years and years of conservation efforts. Mainly by non indigenous folks. So as an indigenous person, we have been intervening for thousands and thousands of years and directly managing the land. So for example, a lot of the prairies in California only exist because of the constant yearly burning by tribes that then was beneficial to like elk and deer and also allowed a lot of wildlife habitat to bloom, such as certain grasses and flowers that need the fire in addition to keeping the fuel load so keeping like all the stuff that builds up low because it's being burnt every year. So we have less of these huge fires. And so for me there needs to be that intervention because that's what there always has been as long as there's been indigenous peoples on this land. And yet there's been this almost mythological lie about wilderness needing to be untouched and pristine. And that mainly comes from a lot of white male explorer clubs such as the Sierra Club with their initial founding and Theodore Roosevelt who did great things with like starting a lot of the current day conservation movements and creating the National Park System. But the flip side of that is many of them did not like Native Americans and did not believe pretty much we were intelligent enough to be specifically managing these complex systems. And so I always say that North America was not bountiful because of lack of human interaction, but because of the interaction of indigenous peoples here for thousands and thousands of years. And so I would like to work more towards getting back to that interaction in a healthy way.

[00:10:55] Speaker B: So now you're pursuing a PhD in the environmental studies department at UC Santa Cruz. What's the focus of research? And you've got this phrase connecting water rights and Native American knowledge through engineering, public policy and social action. And what does that mean in terms of your thesis and in practical terms?

[00:11:18] Speaker C: Yeah. So for the environmental studies program you have to have a natural science and a social science component and a social science and policy component for my minor. And which is really cool because it's super interdisciplinary and very different than engineering and. Right. You asked before, like why maybe I wasn't going to the biology side. Aside from the fact that like I do much better in calculus classes and biology classes usually, but aside from that, the understanding that now I'm getting those pieces that have been missing previously from my education and combining it with this understanding of mathematics, infrastructure and policy from my previous work. And that looks like me trying to look at spring and fall Chinook salmon on the Klamath River. So up until recently, the spring and fall salmon have been considered one species on the Klamath, at least by Western policy. And I'm Trying to get them separated, because in my languages, in the Kuk and Yurok tribes, they have two separate words. And it's shown a lot of times in indigenous languages that separate categorization through language actually aligns very well with differences in behavior. And for me, in my tribe, culturally, the spring salmon play a really important role. And actually one of the translations is loosely like the really good tasting salmon. And so in my mind, one, that's definitely the one I want to protect for selfish reasons, but two, to me that signals that if something's good tasting, right, what tastes good? Fats, butter. If you've been to a restaurant or you cook at home, you know, if you add a little extra butter, it tastes that much better. And so I thinking that there's a nutritional difference between spring and fall salmon. And that's why I'm looking at the DNA between the spring and false neck salmon by collecting samples over two whole years and also looking at the different nutritional components. So I'm pretty much taking sections of the meat, sending it off to a lab, and they give me like a food label back pretty much. And looking at these alleles, so these pieces of the DNA, that should tell me if it's going to be most likely spring, fall, or a combination of both. And one of the exciting things about this research is that there's a lot of theories that say that the spring salmon habitat was actually behind the dams. So the dams have been blocking off about 400 river miles of salmon habitat. And so for all this time, the salmon who might have been breeding up or past the dams have not had the opportunity to. But now with the river opened up, they do again. And so I want to make sure that we protect that diversity in the genes so that when things like climate change happens and there's more extreme weather events, the salmon has more diverse DNA, meaning that they'll be more likely to survive long term when there's these large weather events or differences in climate that's happening more regularly over time. So, long story short, I'm basically collecting samples of salmon DNA and meat and looking for those differences between the spring and fall Chinook salmon to try to prove they're different. And then hopefully going into policy with that to show that they're different, to be like, hey, this is how maybe we should change these policies to better protect this biodiversity. And also to then do interviews with tribal members throughout the Klamath river basin with my tribe, the Yurok tribe at least, and ask them about what they see. The differences are what their grandparents Said the differences are between these two salmon and catalog that and see, say, make this connection, being like, hey, tribal members are saying these are the differences, such as, you know, maybe the shape's different or the color's different. And then I'm also taking pictures of each of these fish and then going to compare them and try to make that connection between validating traditional ecological knowledge within the tribe and this more modern academic genotyping ability and nutritional analysis. So how they're related.

[00:15:21] Speaker B: You're listening to Sustainability Now. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschitz, and my guest today is Brook Thompson, who is a restoration engineer for the Yurok Tribe as well as a PhD candidate in environmental studies at UC Santa Cruz. And we've just been talking about what inspired her to go into civil and environmental engineering and something about her research on salmon. And I'm actually a bit fascinated by the fact that you're doing this, I guess, physical and genetic testing of the two runs of salmon, the spring and the fall. And I don't know if our listeners, all of our listeners know about salmon and their spawning. Maybe you can tell us a little bit about how salmon behave and why there's a spring run and a fall run.

[00:16:11] Speaker C: Yeah, I think that's a great idea. I. I grew up with it so much, I forget that people might not even know. So at its most basic, Chinook salmon and the Klamath river. And most salmon, they grow up in these streams throughout the river. And then when they get a little bit older, they make their way out to the ocean about 1 years old. And then they really cool because. Right. They're freshwater fish that then transform into saltwater fish where they live in the ocean for about two to seven years with the trend because of a lack of food in the ocean, being younger recently. But, you know, after a few years, the salmon come back to the same river and they use their sense of smell to actually go all the way back to the very stream where they were born in to then breed and have their eggs and kids. And that is super cool to me because one, that's like the equivalent of you being born in, like, your childhood home as a baby, your family moving to another city. Say, like, you're born in Santa Cruz. Your family moves to, like, let's say, Portland. And then just with your sense of smell, after living in Portland for, you know, two to seven years, you walk all the way home just with your sense of smell back to the same house you're born in. Like, that's a pretty amazing Feat and also changing from fresh water to salt water back to fresh water. But the thing I'm looking at is the time they're coming back. So the salmon season can be all the way from as early, even this would be really early, but as early as February through November. And with different runs happening. Right. It's not, like, evenly throughout the entire time. There'll be different pushes depending on when the salmon feel like it's best to come back. But traditionally, there's, like, these two main runs. So all these salmon that come back earlier in the year, so like, around March, April, and then all these salmon that come back later in the year, say, like, September, October. And my understanding is, like, historically, these would be very separate, but because of fishing practices, because of habitat destruction, because of how our hatcheries have been working and focusing on fall salmon and removal of barriers in the river that were blocking these two runs physically, they have dwindled in size. So the spring run used to be the biggest run in the Klamath, and now it's the smaller run. And if you think about, like, my tribe, who mainly sustained herself off of salmon, it was really important for that spring run to come because you're just getting out of winter when you don't have as many food available.

And that spring salmon really gave us a push to survive, and that's when. And we have, like, a whole ceremony around spring salmon. And so, yeah, that. Those are the differences in, like, the run timing. So it might be a little bit of nature, but also, like, a lot of genetics on why the salmon choose to return at a certain time of year.

[00:19:07] Speaker B: Well, let's talk about the Klamath river for a bit. Okay. Where does it run exactly? And what's its historical importance for the Yurok, Karok and other tribes in the region?

[00:19:19] Speaker C: Oh, well, I mean, so the Klamath river starts in Klamath, California, which is where I lived for a very long time, where my reservation is. So it's about two hours south, or even just like an hour and a half south of the Oregon border, right on the coastline, surrounded by redwood forests, sandy and rocky beaches and mountains, and in this pretty remote area that I grew up in. And then it runs all the way up through Oregon, and it ends in Klamath Lake in southern Oregon. And with that, you ask what the river, I guess, means to my tribe. So to. To give, like, a.

[00:19:59] Speaker B: In addition. In addition to the. To the fishing. Right. I mean, I assume there's much more cultural significance to the river than this. That. So.

[00:20:08] Speaker C: So I Mean, the river is kind of everything. Like the. Like, even the Yurok and creek names, like, my tribe's names translate to upriver people and downriver people. And so, like, if that says it gives you a hint of how important the river is to us, that's a little bit of it. But I mean, like. Right. It's not only, like, a practical thing in the sense that that's where a lot of our food come from. I see the river as, like, a grocery store growing up, or that's where I got salmon, lamprey, sturgeon, seaweed. There's just, like, so much food you can get from the river mussels that it's a grocery store. It's also a highway because all our villages are along the river, and because it's really mountainous, that's how you get from village to villages through canoe. And so it's our highway, it's our grocery store. It's also a spiritual being. So there's a spiritual importance. And actually, the tribe a few years ago gave legal recognition of the Klamath river to have personhood. So we can sue on behalf of the river if needed. And, yeah, so for me, the river is also kind of like a family member. Like, it. It's my past, present, and future, because kind of like I said, with the salmon, to me, the river is the closest thing I can get to a time machine where if I take care of these salmon, I can send that love and care into the future for, like, my future great grandchildren who will then have the opportunity to have the salmon. So also a time machine.

[00:21:30] Speaker B: So there were. There were four dams on the river, right? Or there more than four.

[00:21:34] Speaker C: There were six dams with four.

[00:21:36] Speaker B: And when were they installed and. And for what purpose?

[00:21:40] Speaker C: So the lower four dams were installed specifically for hydropower production and meaning that they were using it to have turbines to create electricity. And the dams have been around. Built between, like, around 100 years ago and the last one being finished in 1962. And so which is the year my dad was born.

Sorry to anyone who knows my dad to give out his real age, but yeah, so that's when the last dam was built, which was. Iron Gate was completed around then.

[00:22:11] Speaker B: And. And who. Who owned the dams and who got the electricity?

[00:22:15] Speaker C: So the dams went through a few different hands of ownership throughout the years, but the last owners before they were turned over was Pacific Corps, and Pacific Power, who is a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway, and the surrounding area got the power. But one of the things about dams and hydropower is that when you have dams, what creates the power is the change in height and the flow. So when a dam is there, it blocks all the sediment, so all the soil and stuff from going downstream that it normally would. And because of that, over time that piles up and the dams become less efficient. So the dams, the longer they were in there, the less power they're actually generating over time.

[00:23:01] Speaker B: You mentioned Berkshire Hathaway, the shirt people, right?

[00:23:06] Speaker C: What's his name? Who owns.

[00:23:07] Speaker B: Yeah, Warren Buffett.

[00:23:08] Speaker C: Yeah, well, the Warren Buffett guy.

[00:23:10] Speaker B: But I always think of Berkshire Hathaway as shirts. So it's interesting that they own a lot of things. Yeah, I know. And how did the dams then? I mean, it's obvious that they obstructed up river spawning. But. But more broadly, what were the impacts of the dams on salmon and lampreys and other fish and on the traditions, the practices of the people living along the river.

[00:23:36] Speaker C: I'll just have time to go into a little bit of it. But basically, like you said, it blocks the salmon passage from breeding behind the dams. And there's other species that go up and down the river too, such as lamprey, who also weren't able to get up that far. There is also the fact that there is parasites that have killed the salmon, such as sea. Sea Shasta and Ick and for example, a sea Shasta. The part of that life cycle is through these worms that grow. And the worms kind of like this really specific type of water and water that's not moving too quickly. And so the dams create this like perfect breeding ground for these worms to grow, which then there's more worms, there's more likely to be parasites in those worms, which means they're more likely to spread and then kill the salmon and so increased parasites. The dams also hold back water, which makes it stop moving. And when you don't have water that's moving, it's in that hot. Whereas an organ is kind of deserty. So like this hot desert sun, you get really hot stagnant water and then you have some extra nutrients from like farming up there. And with phosphorus, nitrates and nitrogen that kind of create this perfect breeding ground for blue green algae. And a lot of this algae had toxic blue green algae with it or mixed in with other types of algae. And this toxic blue green algae made it. So when the dams were open and water was released downstream, all this toxicology would go with it and make it so that the water was pretty much unswimmable. So I used to grow up swimming in the river all the Time. And then as I got older, there's all these signs posted along the river saying you can't touch the water. And if you do, you're supposed to wash your hands. And you can't let dogs drink the water, your kids near it, because it might be so harmful they might die. And I've known multiple tribal members to be hospitalized because of contact with this toxic blue green algae blooms in the water that were made much, much worse than they were historically because of the dams. And so, you know, even as fishermen, again, a lot of our diet still comes from the river because I can't afford the same salmon in a supermarke market that I could get in the river. When the fishing was good, we were selling our salmon to middleman for like $5 a pound. And in my dad's generation, it was even less, like $1 a pound. And now, like, even back then when we were still getting a lot of salmon, I saw the same salmon that I sold as in like the same middleman selling to places in Portland, Oregon, like zoo pans, grocery store, selling for like 35 a pound. I could never afford to eat that salmon. And so we talked about like, the hot water also, when that water gets warmer too, it holds less dissolved oxygen, which is what the fish breathe. And so the fact that there's less dissolved oxygen makes it more difficult for the salmon, which stresses them out. And if they're stressed out, they're more likely to get diseases. And it's just like this all intertangled web of multiple ways that having the dams stress out the fish and can be harmful to people because also. Oh, what I was saying is, like, we still need to get the fish from the river. So even then, like, we still have to expose ourselves to that toxic blue green algae. Like, even my dad would get these rashes on his arms from touching the water. And it's just something we had to live with.

[00:26:52] Speaker B: Tell me, were there anything, were there fish ladders around the dam?

[00:26:56] Speaker C: No, there are no fish ladders on the dam.

[00:26:58] Speaker B: There are no fish ladders. So the, the salmon could not get up into the upper lakes, right into the lakes behind the dams. So they were basically restricted to the stretch of the river below the, the, the lowest dam, right. The, the one closest to the ocean. But did the water then, was the water draining, you know, through the, the turbine? Is that what was, is that what they were exposed to and you were exposed to?

[00:27:27] Speaker C: Yeah. So there's the spillway and the turbine that water gets released through in the dam and. Yeah, so it's that water that's coming off kind of the surface of the dam that's getting drawn down and pushed downstream. So there is flow, but it's not.

[00:27:44] Speaker B: It'S not as rapid as it would be otherwise.

[00:27:47] Speaker C: And it still like, has that algae and it still has that hot segment. But yeah. The lowest dam on the Klamath river was Iron Gate, and the largest dam, and that's the one that was built in, finished in 1962, and that had no fish passage whatsoever to any fish species.

[00:28:03] Speaker B: You're listening to Sustainability Now. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschitz. My guest today is Brooke Thompson, who is an environmental and restoration engineer up on the Klamath river and is also doing a Ph.D. in environmental studies at UC Santa Cruz. And she is author of a children's book, I Love Salmon and lampreys, which we will talk about in a bit. But, but right now I'm trying to. We're trying to understand or talk about the spawning of the salmon in the lower part of the Klamath River. So the salmon were only swimming up as far as the. As Iron Gate. Right. But they were still spawning. Were they able to spawn under these kinds of conditions or what was happening? Exactly.

[00:28:49] Speaker C: So they've been able to spawn, but a lot of the population has been artificially supplemented through hatcheries along the Trinity and up the Klamath River. So, right, you have these wild fish species, but also like the interbreeding with these hatchery species in the hatcheries along the main Klamath river, we're only focusing on fall salmon. And, and that's because when hatcheries it's hard to get that diversity you'd get in nature. And so it's almost easier when the genetics are similar because then you can treat them all the same and have a bigger quantity.

But the quality of the genetics is not necessarily at the same level. But yeah, they've been able to spawn. But then there's also the issue of all the streams, right, because they go up the main stem of the river, but then where they're actually spawning is these smaller streams and tributaries. And a lot of those have been destroyed or aren't as good of quality because of the history of removing large wood because of gold mining, etc.

[00:29:55] Speaker B: Well, let's talk about now the dam removal project. So my understanding is it began about 20 years ago when you would have been what, about 12 or something like that?

[00:30:07] Speaker C: Well, yeah, so it, I think when the first push happened was when that 2002 fish kill happened, which was when I was.

[00:30:15] Speaker B: Can you tell us about that? Because of course, it's, it's a, it's the largest project of its kind, the removal of those dams so far. And how did it, you know, how did it proceed? I mean, it, it. For a long time it seemed like an impossible dream.

[00:30:32] Speaker C: Oh, yeah. I mean, we have seven hours, right, to go through the history. No, no.

[00:30:37] Speaker B: You know, Yeah, I, Yeah, if we did.

[00:30:39] Speaker C: But yeah, the, the footnotes of it or like the spark notes would be that.

[00:30:44] Speaker B: And.

[00:30:44] Speaker C: Right. I was a kid at the time, so this is my recollection as like a seven year old, is that there are a lot of people coming together that basically were. We're coming together through this idea that this cannot happen again and that we have the science to show that these dams are harmful.

And because it's. To me, losing salmon and having poor water quality equals like loss of life in my tribe. Because right. When you don't have those healthy foods, you have hard, like higher cardiovascular disease, higher diabetes rates, and also higher suicide rates because you have like that loss of culture and you have the people dying from those other diseases, from having unhealthy diets or. The river was like my gym. I was swimming in it, I was fishing in it. All of a sudden I didn't have access to that. So that also leads to those different issues, health wise. And then when you have people passing away from you all the time and you don't have access to those healthy foods anymore and don't have that connection to ceremony that the salmon also help with, you have increased depression. And so for me, when the water does bad and the salmon does bad, I literally have people around me die. And having those kind of stakes where I don't think everyone else realize how impactful losing the salmon was for us and still is that people came together and were trying to just figure out all these different ways that they could go about getting the dams removed, whether that be through protests, through rallies, through meetings, through policy, through lawsuits. And it took a lot of different parties, pushed by the tribes, mainly on the Klamath river, but then support through conservation organizations, through lawyers, through academics and researchers and politicians and policymakers that after many agreements failed, talks, talks that we failed but learned from, and protests and rallies. There's even people who went all the way to what's his name? From Berkshire Hathaway, Buffett, Warren Buffett went to Warren Buffett's house and like, protested in front of his house. And even, like me, I'm a Gates Millennium Scholar, which means Bill Gates helped pay for part of my education. I know there was a push even with the Gates Millennium Scholar, since Bill Gates is a like a secondary shareholder, Berkshire Hathaway, where we wrote notes as Gates Millennium Scholars to him, asking that he pressure Buffett to let go of the dams. And also through proving that it was actually financially more feasible to remove the dams and it was for the company to keep them up. And so all of that together made us be able to finally remove the dams just this last year after like the 24 years of pushing since 2002 to 2024.

[00:33:38] Speaker B: I'm curious, what was the financial argument, if you can, can you recapitulate that?

Because, right, the power company was selling electricity and presumably the cost, they had maintenance and operation costs, but the capital costs I'm presuming were, were paid off. So why was it. Would, would they do better taking out the dams?

[00:34:02] Speaker C: Yeah. So I'm going to put a little asterisk here just because I'm not a financial person. I don't have all the details, but my understanding with the financial aspect is that the renewal of the license of the dams would have been one of the major components why it was more expensive to keep them in versus remove them. And part of that might have been to install a fish ladder, which would have been incredibly expensive. In addition to what you were saying about like maintenance upkeep and the fact how I said earlier that over time the dams produce less and less hydropower and electricity.

And that altogether wasn't making sense with what they were actually making from the electricity. And so it would have been cheaper for them to remove the dams completely than it would for them to renew the license and continue upkeep and meet current standards.

[00:34:55] Speaker B: My understanding was that there was a fair amount of opposition to, to the project from people, you know, not, not the tribes, but other, other people living around the area who was against it.

[00:35:09] Speaker C: And I mean, I, I can't say for sure because I don't. A lot of those groups aren't like a monolith, in my opinion. It's a lot of like, upper basin folks and I understand their concern to an extent because. Right. A lot of these people have homes that were along the river or that are along the river, were along the lakes. And so they wanted this lakefront property and they're afraid of how that might like, change their property values, for example, or change the water level in their wells, etc. And I honestly think a lot of the opposition was caused by misinformation.

And honestly, I Think part of that is, I mean, I can't talk about anyone but me, but like, I think in general, not only in this project, but, you know, engineers, scientists and people doing this work could probably do a better job at talking to the public. Because sometimes I feel like we use language that's so complex that, like, when you have someone else who's saying like kind of a conspiracy theory that's like really straight to the point you're going to listen to the one that makes sense to you versus, like these government people who don't live in the area, coming in and saying all these like complex ideas and things that may or may not be true. And so for me, I think, is a lot of that miscommunication. And actually res, who is the contractor for like the restoration projects, I think did a really amazing job at hiring a local named Ren who did the PR for the dam removal. And she worked so hard to bring people to the dam sites to actually show them what was happening firsthand. And I think that changed a lot of people's minds. So I give her major props and especially how tirelessly she worked. But also I think it's just. Change is scary. Right. These people have been living on the river a long time too. Maybe. I mean, maybe not. Definitely not as long as us from the tribe. But you know, when you have these major shifts that are happening that they don't necessarily like have say in or don't have understanding, I think it's natural to be. To be concerned and to have fear. Right. But since then, I've heard a lot of people be very pleased in the area from the outcome.

[00:37:25] Speaker B: Yeah. You know, I saw photographs of what, you know, after the dams were removed and all of the sediment and silt went washing down river and it left behind kind of a denuded landscape, it looked like. So what's going on there in terms of restoration efforts?

[00:37:44] Speaker C: Yeah, So I can only speak on a bit of this because that's fine. Yeah, than the part of the team. But basically what's happening is RES is partnering with, for example, the Yurok tribe and other groups to do revegetation in the area. So, for example, some of the things I got to do was take out invasive species before the dam is removed to make sure they weren't going to spread too quickly.

Like a crazy amount of pounds of seeds were collected to spread over the area of native plants. And these plants were specifically collected from the area. So they'd have like the genesis, kind of like the salmon I was talking about. Who are Evolved to live in a very particular place. Same with, same with plants. They collected local plants so they were perfect to kind of survive in that area already.

And I got to collect like acorns to that are going to be replanted in the area where they'll have these oak trees grow long term, where we're expecting willows to grow back. So pretty much that area that opened up, that was previously under the lake is a great opportunity to get these native plant species in and make sure the invasives don't take over so we can have this thriving habitat around the river for the other species like birds and wildlife.

[00:39:01] Speaker B: How long, how long is this, this, the restoration project going to take?

[00:39:06] Speaker C: I love that question because I probably have a different answer than other people. I mean, the company res is contracted for quite a few more years because it takes time for like these plants to settle and grow and get into place. But for me as like an indigenous person, I don't think restoration is ever over. Right. It's that kind of reconnecting with the environment I was telling you about where I think us as indigenous peoples and just people who live on or by these areas of land will always have a responsibility to take care of it. And in that sense, the restoration is going to be ongoing.

[00:39:41] Speaker B: So it's a lifetime project for you?

[00:39:43] Speaker C: It sounds like it's a multiple lifetime project for me. Well, to restore it and that they want to restore it. I mean, that's one of the reasons with the children's book. Right. Is to me that's how you communicate better with the general public, is to simplify things down to a kid's level. If I'm like, if a 4 year old can understand it, I'm hoping an adult can understand it.

[00:40:02] Speaker B: Yeah, well, it's like the old Groucho Marx joke. You know who Groucho Marx was?

[00:40:06] Speaker C: I don't.

[00:40:07] Speaker B: You don't know? Well, there's a line from one of his films in which he says, you know, this is so simple. A four year old could understand it. Run out and find me a four year old.

Some of my listeners will, will remember that and others won't.

You're listening to Sustainability Now. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschitz. My guest today is Brooke Thompson, who is a member of the Yurok tribe and an restoration engineer for the tribe on the Klamath river from where four dams were recently removed and the river banks are now being restored. The river and the riverbanks are now being restored to accommodate native wildlife, including salmon that swim up the river to spawn. But Brooke has also written a children's book. And why don't you tell us something about that and why you did it and what's in it?

[00:41:03] Speaker C: Yeah, so I wrote a children's book called I Love Salmon and Lamb Praise. And it's basically my life story on growing up on the Klamath river, seeing the salmon die in 2002, what dams are, why they were harmful to the salmon, and how we got from there, through protesting and through working together to having the dams removed. And the book's age is for about 4 to 10 year olds. And for me, I wrote this book because I wanted a way to tell my younger cousins a story, because it is not every day you get to make the impossible happen. Right where the adults, when I was a kid were told that this was an impossible dream, that maybe one could be removed potentially, if even that. But asking for four was insanity. And yet it's happened. I've seen it with my own eyes that the dams are gone. And seeing that accomplishment, I'm also hoping creates this sense of hope in children because there's so much eco anxiety and fear with the future, with climate change, that I also want to give that sense that change can be made and that when there's something that we really believe in and work towards that, despite what we're being told, if we know it's something that needs to be done, we can come together and do it. And so it's to have this story of hope to be able to explain to my younger cousins who now have the privilege of not growing up with the dams, who will never have the dams on the Klamath river, at least those four that were causing so much issue. And be able to also tell the story of me going to college because I didn't grow up with a lot of natives going to college when I was growing up, and especially in engineering and, you know, not just natives, but I never got to see many women or women of color or people of color in engineering, even when I was in my classes in engineering school. And so also having that representation. So I have always wanted my try my best to be a good role model to my cousins.

And this is one of the ways I feel like I can do that even when I'm not with their. Them physically, or even my cousins or my family maybe that I don't know are my family yet. Like all the more extended idea of family in Turtle island, where, you know, I can have that type of representation where they can see a native woman go to college and use that information to come back to their community and help save the things they care about. So those are just a few of the reasons I wrote the book. In addition to it being an open dyslexic font, which means the font of this book is written in a way or shaped in a way where it's easier for kids with dyslexia to read. And I have severe dyslexia. So growing up, I often did very poorly in writing and reading and got in trouble for it. And so it's also kind of that sense of pride for me being like, despite this disability that's been difficult for my entire life, being able to write this book that's, you know, being able to write a book with dyslexia and then also have something where kids who have similar disabilities can have an easier time reading it. And because I never had something like that growing up. So it's kind of all those reasons combined and why I wrote this book. And kind of like you were saying too, like, or we were talking about earlier, with it being difficult sometimes as scientists and engineers or lawyers to talk about these complex problems, it's just a good exercise to be able to tell the problem in a very simple and straightforward way.

So again, like we were talking about earlier, you know, if a four year old can understand it, then hopefully an adult can understand it. And I looked up. His name's Gucco Marx. Is that you say?

[00:44:54] Speaker B: Groucho Marx?

[00:44:56] Speaker C: Oh my gosh, you can see how young I am. I'm in my 20s.

He's. He's the guy with the mustache.

[00:45:00] Speaker B: Yeah, he's the guy with the. Yeah, the toothbrush.

[00:45:02] Speaker C: I have, I have seen my dad watch something like that.

[00:45:04] Speaker B: Okay, okay.

Who, who illustrated the book?

[00:45:09] Speaker C: The book was illustrated by Anastasia. So the, it was a collaborative process which is actually kind of unusual for children's books. And so I, I drew the layout and then she did the watercolor with reference pictures I gave her. And then we went back and forth with edits.

And so she, she did this beautiful watercolor and she is actually lives and is from the Ukraine. And I sought out an illustrator who could potentially use why I had this funds to who could use some money. And I figured, you know, with the war going on that her as a Ukrainian woman could probably use the extra funding coverage.

[00:45:50] Speaker B: So look, you know, this is a, this is a landmark project, right? And there are dams around the world that are probably primed for removal, but of course won't be removed just because the momentum is not in that direction. How would you go, and this is a complicated question, but how would you go about supporting and maybe facilitating dam removal elsewhere? What lessons have you learned and that might, you know, support doing this?

[00:46:29] Speaker C: Yeah, I love that question. And Right. That's part of. Is bringing this back from the tribe and looking at this more global scale of what's happening for the larger scale. Actually, that's one of the things I've been focusing on is with the United Nations COP meetings.

So I. I went to the one in Cairo or. Yeah, I went to the one in Egypt, non Cairo, but in Egypt two years ago. And I'm planning to go to the one in Brazil this upcoming year. And I talk about the pros and cons about hydropower and how there's actually a lot of negative environmental consequences to these dams. Like other places, dams create a lot of methane, which is a greenhouse gas, because of that storage of water. And for me, it's not only how do we remove dams and the pros and cons of that, but also there's a lot of dams that are being built right now to try to meet energy goals because hydropower is considered a renewable energy.

So one of my goals is to have, hopefully, countries slow down on building these dams a bit and consider where they're putting them, how we can manufacture and engineer them in a more sustainable way. Because a lot of the dams are being put in places that are displacing and mainly hurting indigenous groups around the world. And it's much easier never to put up a dam than it is to remove a dam. And so I think some of the lessons learned here is that one, it can be done, two, it can be beneficial financially and socially and environmentally.

And three, that maybe we should reconsider the way we've been engineering these dams in the first place, because I do believe that there's better technology out there and that we can be more considerate, especially when it comes to, like, fish ladders for other species.

And honestly, if I were to change the world of engineering and dams, I would say that we should be considering how to remove the dams when we design how to build them. Because dams, they have a long life, meaning they have a long lifespan, but it's not forever. Like, dams are designed to last about 80 to 150 years and it has to be removed at some point. Dams cannot be in the places they are infinitely. And so I really think that we should be considerate to future generations and thinking about how we're removing them sustainably in the future. Before we build them in the first place.

[00:48:58] Speaker B: That's an interesting point. Are there any other projects, dam removal projects that you know of going on around the world?

[00:49:07] Speaker C: Oh, yeah, gosh, I having trouble thinking of them off the top of my head, but I know some other tribal groups and dams they would potentially like to see removed is for example, Bonneville Dam, which was an area that was taken from tribes in Oregon, northern Oregon, during World War II, where they were.

[00:49:27] Speaker B: This is on the Columbia, right?

[00:49:28] Speaker C: Yeah. Where they were promised their fishing spots forever as part of their treaties and it was taken from them. And then there's also dams on the Eel river that are being petitioned to be removed right now too. And I also personally, I think the Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado should be removed. So those are just a few, but there are many more. And I think people are getting more and more excited about dam removal because of the success of the Klan with dam removal and. Right. The success of the climate dam removal also has to do with the success of the Elwha Dam removal, which was the largest dam removal before this one.

[00:50:07] Speaker B: Well, it seems like maybe the next children's book should be a Action Guide to how to remove dams since since they seem to be 20 year projects. Right. You start young and then I'm hoping.

[00:50:22] Speaker C: They won't be 20 years much longer. I'm hoping we're gonna make the process quicker from now on.

[00:50:27] Speaker B: Okay, well, we're at the end of our time together. Is there anything else you'd like to mention?

[00:50:34] Speaker C: I think if I could just, you know, plug some of my social media that if you want to know more, you can message me on my website, which is brookmthompson.com B R O O K M T H O M P S O N I have an Instagram Tick tock, Blue sky, all the good things. And yeah, please check out my children's book because buying that book also helps support me and my research and just that, you know, I can only speak for my own experience, not my other tribal members experience, and that there is hope out there. There is a lot of people doing good work to protect the environment. And I know it's easier to focus on some of the scary things happening in the world than it is the positive. But that I'm out here celebrating the dam removal and that my tribe and all these people did the impossible and I just want to pay my respects to all of them because I played a very small part compared to everyone who came together to make this a possibility and that I'm nothing without my community. So thank you to everyone.

[00:51:35] Speaker B: Well, Brooke Thompson, thank you for being my guest on Sustainability now.

[00:51:39] Speaker C: Yeah, thank you so much for having me. It was a pleasure.

[00:51:42] Speaker B: You've been listening to a Sustainability now interview with Brooke Thompson, a member of and restoration engineer for the Yurok Tribe in Northern California on the Klamath River, a PhD candidate in environmental studies at UC Santa Cruz and author of I Love Salmon and Lamprease, an illustrated book for children about the Klamath Dam Removal Project.

If you'd like to listen to previous shows, you can find

[email protected] SustainabilityNow as well as Spotify, YouTube and Pocketcasts, among other podcast sites.

So thanks for listening and thanks to all the staff and volunteers who make K SQUID your community radio station and keep it going. And so until next every other Sunday, Sustainability Now.

[00:52:36] Speaker A: Good planets are hard to find. Now. Tempered zones and tropic climbs and run through currents and throw robbing seas, winds blowing through breathing trees, strong ozone and safe sunshine.

Good planets are hard to find. Yeah, good plan.