[00:00:08] Speaker A: Good planets are hard to find. Now, temperate zones and tropic climbs and run through currents and thriving seas, winds blowing through breathing trees and strongholds on safe sunshine.

Good planets are hard to find.

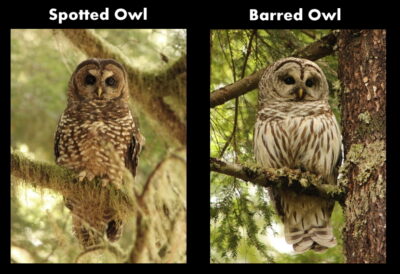

[00:00:35] Speaker B: Hello, k squid listeners. It's every other Sunday again and you're listening to sustainability. Now, a bi weekly case good radio show focused on environment, sustainability and social justice in the Monterey Bay region, California and the world. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschitz. Do you remember the northern spotted owl, icon of the old growth redwood wars of the 1990s? Well, the northern spotted owl is once again under threat. This time, however, the threat comes from another species of owl, the barred owl, a larger and more aggressive bird native to the United States, whose range has been expanding westward as a result of development and climate change. The US Fish and Wildlife Service has devised a plan to protect the northern spotted owl, shoot barred owls. Scientists, conservationists and the public are tornado. Should humans intervene to prevent animal extinctions by competitors and invasive species if they threaten the survival of endemic ones? Or should we let nature take its course? And since humans have intervened in nature for thousands of years, every day and everywhere, what is the right thing to do? How can we decide? My guest today on sustainability now is Hugh Warwick, spokesperson for the British Hedgehog Preservation Society, an ecologist who has been looking into this dilemma around the world. He's just published cull of the wild killing in the name of conservation. Warwick is a frequent speaker on wildlife conservation and public talks and on british radio and tv. He also runs courses on hedgehog conservation. Hugh Warwick, welcome to sustainability now.

[00:02:13] Speaker C: Thank you.

[00:02:14] Speaker B: Before we start, I've read that you do stand up hedgehog comedy, and I'm wondering whether you might have a hedgehog joke at hand that we could start with.

[00:02:26] Speaker C: Well, it tends not to be gag laden, more situational. And often. Sometimes, I should say, at the expense of the hedgehog pet keepers of North America, because I have had the great delight of being invited to the Rocky Mountain hedgehog show one year and staying there for the international hedgehog Olympic Games, which I did really think was made up, but clearly isn't. And so, yeah, why did the hedgehog cross the road?

[00:03:00] Speaker B: To lay it on the line?

[00:03:02] Speaker C: No, to show we had guts. But anyway, that joke works better if you're familiar with the road casualties in the United Kingdom.

[00:03:10] Speaker B: Yeah, right. As Molly Ivins once said, the only thing in the middle of the road is roadkill. But she was talking about politics.

Well, listen, let's get down to business, okay?

Why don't we start with some background information how did you get into this, into this business? And by that I mean broadly, wildlife conservation and hedgehog protection.

[00:03:36] Speaker C: Oh, that. It's innate. I mean, I have, it's an interesting sort of look at nature versus nurture. I was adopted as a baby and my parents who brought me up weren't particularly interested in nature, but I was always passionate about it. I was always fascinated by wildlife, in particular mammals. Peculiarly, I didn't really catch the bird bug. I never really got that fascinated by botany or entomology. It was always mammals. And then in my mid thirties, I met my biological mother for the first time and we're now very close friends and it turns out that her nickname at school was badger and that she's always had this deep love of nature. So I really believe that it was innate.

It depends how far back you want to go, but in terms of more practical things, that innate love of nature had me yearning to become a vet until I realized you had to be really clever and be able to pass exams to be a vetted. And I was not particularly good at that sort of thing. I mean, good enough to go on and do a masters in wildlife management. But along the way I started to do practical bits of study, initially on hedgehogs, and that just opened the door to the fascinating world of ecological research, which then inevitably led on to the conservation side of it, because when you become aware of what's going on, you recognize things need to be done differently.

[00:05:12] Speaker B: Well, I mean, it's interesting, though, that, you know, in your book you cover a wide range of wildlife management situations, which we'll get back to in a second. But I gather you initially were noted for your hedgehog Filia, right? That would be the right term, I.

[00:05:33] Speaker C: Think, if you're going to go to the.

[00:05:36] Speaker B: What happens? I mean, do people say, oh, well, you, you know, he's, he's, he defends hedgehogs, but let's ask him about this other, you know, this other beastie.

[00:05:46] Speaker C: Well, you become known as a sort of person who knows about animals and a lot of people will assume you know about more than one animal, I should say. I have written books on other animals, too. I've written small monographs on water voles and on beavers and I wrote a book called the. There we go. Let's get this, the beauty in the beast, where I went and met 15 people a bit like myself. And this was a fantastic trip around the United Kingdom, meeting obsessives who were into otters or robins or moths, bats, owls, and it was my midlife crisis in one book, as I was looking to get a tattoo to go next to my hedgehog tattoo, and. But it was a really lovely sort of exploration of the natural history of a whole different range of species.

Pardon me. So I love. I should. I love all nature. I mean, I really, really do. I use the hedgehog mercilessly. But actually, in my garden here in Oxford in England, I have each year now, for the last few years, tamed a robin. It's not the same as your robin. Um, ours is the original robin and beautiful red, well, orange breasted bird. I've tamed them to come and land on my hand to take mealworms or cheese. And I've had some of my best wildlife moments in those points of connection. And. And yes, I am known for it because I advocate, I talk about. I write about these things to anybody who'll listen.

[00:07:26] Speaker B: Well, you're also spokesperson for the British Hedgehog Protection Society, and I was wondering, what are you called upon to do in relation to that?

[00:07:37] Speaker C: Well, the British Hedgehog Preservation Society was set up in 1982.

Major Adrian Coles had retired from the army and moved back to Shropshire and found hedgehogs dead in cattle grids. They got stuck, they dropped in, they couldn't climb out. And so he started putting bricks in them to let them climb up, up through the staircase and started a campaign. And hence the society started.

So the society has always been involved with the sort of conservation and protection of hedgehogs, but also helps raise awareness for and support of the hedgehog hospitals, the wildlife hospitals around the country. My role as a spokesperson, I mean, I don't. Haven't really got a job there. I'm just called upon when the media calls. And the chief executive of the Hedgehog Society, Faye, is a really brilliant organizer and really shy.

I'm quite chaotic, but a show off. And so, between us, we actually do quite well.

[00:08:36] Speaker B: Okay, well, let's get to the issue of conservation, wildlife conservation. Now, we're frequently told the earth is in the midst of the 6th great extinction caused mostly by human development.

Your focus, at least in the book, is primarily on the depredations inflicted upon indigenous species by invasive ones. So what is an invasive species? And do you think the term is a fair one, especially since those invaders didn't choose to migrate?

[00:09:09] Speaker C: I think the use of the word invasive is more to do with the description of how they are when they are in place. There's a lot of species which have been moved around the planet which cause no particular bother at all.

And yeah, they've just managed to integrate into their new ecosystems and they rub along fine with their neighbors. I mean, you have lumbricus terrestrial in North America, the humble common earthworm from the United Kingdom, which was taken over there, has totally transformed the ecosystems over there, but nobody's looking to eradicate it. The vast majority of species don't cause trouble. And so that invasive tag is given purely as a sort of commentary on how they are acting. So it's only referring to those species which are causing what some people will consider to be a problem.

And yes, there is a whole host of issues facing the natural world. The reason why I'm interested in this particular story is because it's one which requires active attention. Now everything else tends to require us to stop doing something.

This is something which requires action right now.

[00:10:22] Speaker B: Yeah, well, and the stop doing something is quite difficult, but also very useful.

[00:10:28] Speaker C: If we would possibly to just maybe consider sharing the planet a bit more than just destroying it.

[00:10:35] Speaker B: So why don't you give us an example, a story? Might as well do hedgehogs. I want to ask you later about owls, which you didn't write about, but you know, about which there is a kerfuffle up here in northern California.

But why would anyone want to kill hedgehogs?

[00:10:53] Speaker C: Well, I mean, this is a very good point when I, in fact, the starting point of the book of colour of the wild is hedgehogs. The very first work I did on hedgehog ecology was up on a small island, the most northerly of the Orkney archipelago, small island called north Ronnelsey. It's a mile wide, 5 miles long. And I went up there in 1986 whilst doing my degree and to look at whether the introduced hedgehogs, which were introduced by the postman in 1974, were responsible for the decrease in breeding success of ground nesting birds. Now, the island has no trees and it's got a few stunted things about six foot tall in the middle, but no birds nesting in trees. They all nest on the ground, really beautiful populations of wading birds. But in this particular instance, we were looking at the impact on arctic terns.

So what I was doing initially for my degree was seeing how many hedgehogs there really were, because if you're going to get an idea of what's going on, you need to have a starting point. How many hedgehogs were there on the island?

And that meant I spent my summer holidays counting hedgehogs. And it was a really lovely introduction to sort of life as an ecologist.

I went back up there in 1991, to repeat the work, because I had, by that stage, got the bug and found that it was complicated, as all of these things are. This is one thing which people underestimate, I think, is the complexity of ecology, and it's why only hardcore scientists go into ecology. Lightweights will go off and do astrophysics or something, but if you. It's interesting, astrophysicists. So there's a saying attributed to Ernest Rutherford that the only true science is physics and everything else is stamp collecting and cookery.

And this just really grinds my gears a bit, because we have this situation that as an ecologist, you're out at night in the pouring rain, collecting small amounts of data for nearly no money at all, or no money at all, whereas an astrophysicist sits behind a machine that was built by an engineer, presses a button and then goes, oh, still don't know where 95% of the universe is, can have some more money.

Anyway. So hardcore scientists do ecology. So I was doing the hedgehog work, finding out the fact was that the arctic terns were getting far less food than other arctic tern populations around the country just by sitting for hours and hours and hours counting the sand eels that the birds were bringing into their chicks.

But also at the same time, I was finding eggs in the colonies which had been definitely eaten by hedgehogs. So they were part of the problem. Hedgehogs had been airlifted off the island by the bird observatory, but it wasn't sort of followed up in a scientific way as a random thing. So that one story. Next story. 2003. The RSPB, our big bird charity with the scottish government, started to kill hedgehogs on the outer hebridean islands of the Uists. Initially, I thought this must be because they'd found new science, which meant that there was no way they could be moved. And in fact, they declared that they. They couldn't move them because it would cause slow and lingering deaths. I went and did a. I made a radio program for the BBC while I was up there, went and looked at the work they were doing and discovered they were using some of my other hedgehog work inappropriately to justify killing hedgehogs. So I got grumpy, joined a campaign and ended up doing research which stopped the killing of hedgehogs. At the same time as this, I was at a conference in Germany, hedgehog conference, of all things, and a conservationist from New Zealand turned up to explain why he was killing hedgehogs in New Zealand. And I put my hand up and said, whoa, whoa, whoa. You don't need to kill hedgehogs. And he sat me down, we had a chat and he presented a case which I can't find a solution to. That is why I started the book cull of the wild. Because of this conundrum, I object to the idea of killing wildlife. I think it's horrible. However, in this instance with the hedgehogs in New Zealand, I couldn't see a solution.

[00:15:18] Speaker B: And that's so as you write with an island, there's at least a perimeter within which you can capture the hedgehogs and then do something with them. Right. In a much larger territory, it's much more difficult to do that. You're listening to sustainability now. I'm Ronnie Lipchitz, and my guest today is Hugh Warwick, who was spokesperson for the British Hedgehog Preservation Society and has just published call of the killing in the name of conservation.

I had this note here. You call it. The title of the book, of course, is a play on Jack London's famous book.

But also the use of the term cull as opposed to kill is, I suppose, a propaganda move, or how would you describe it and why cull as opposed to kill?

[00:16:12] Speaker C: Well, in terms of the title of the book, it was simply because cull of the wild stands closer to call of the wild than kill of the wild. But also I'd got, as a subtitle, the subtitle came first, killing in the name of conservation. I mean, I reached out to rage against the machine to see if they'd re record their song for me, but they haven't responded.

And my agent was very clear that even using the word killing in the name of conservation in the title is a big no no. You don't use that sort of negative term and the title of the book. So the title Cull of the Wild is actually thanks to my neighbor, Elon Ezekiel, who lives just across the road, as I was bemoaning trying to find out the solution to it. Cull is a term which is used by wildlife managers, has always been used by wildlife managers, and it is definitely a slightly softer word to kill, as you'll see through the book. Whilst the title of the book is Cull of the Wild, I tend not to pussyfoot around. I tend to be fairly direct with what people are actually doing.

[00:17:19] Speaker B: Okay. Well, I mean, I think it's a great title, and that's just my opinion. I always like titles that include various kinds of plays on.

[00:17:30] Speaker C: But can I just point out then, my previous book, the Beauty in the Beast?

[00:17:34] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:17:34] Speaker C: Well, you see, I've got a theme running here.

[00:17:37] Speaker B: Well, and of course, there's a long, long history of stories of anthropomorphized animals. So I imagine there are lots and lots of possibilities in terms of the future.

How about some other examples of these sorts of conservation dilemmas?

Most of the things that you're writing about seem to me to have to do with predation of birds, but there are, particularly from Australia and New Zealand, there are these other stories, and I think our listeners might like to hear about. About those and why or why not, why they have succeeded or not.

[00:18:26] Speaker C: Well, I mean, it is not just about birds. There is a lot of the bird stuff, because due to issues of money and time, I couldn't do what I'd have loved to have done, which is to fly around the world and go and visit all of these projects in different places. So I was restricted to ferry rides and short hop flights to islands around the UK.

But I did a lot of research, obviously, online and zoom calls in Australia and in New Zealand, both fairly remote places, Australia, with land mammals, obviously, the marsupials and the dingo, they had the massive influx of the colonists from Europe in particular, bringing with them a whole range of species which have been causing trouble. New Zealand, famously, again, I mean, the hedgehog, the people, when they, the colonists, when they arrived in New Zealand, they looked around the place and went, this, this is. This is gorgeous, but it's missing hedgehogs. And they wrote back to England and they asked them to send hedgehogs. And so hedgehogs were sent to New Zealand along with a whole range of other species. And for a long time, the hedgehogs were thought to be the most benign, but now they're recognized to have an impact. They're. The hedgehogs is impacting birds, but also beetles.

It's an insect. It's called grasshopper of some sort. Grasshoppery things, and they eat them. They also eat the skinks, lizards and things like that, too.

So there's a whole host of things which are being depredated by hedgehogs and the other invasive species. Australia is fascinating because it's where there has been the beginnings of some work of the field of compassionate conservation, which is something I'm very interested in. And I would really.

Basically, I think we need more time and money spent looking at the options available for it there. What they found in Australia, the biggest problems come from feral cats and foxes and I. There is a whole host of species of marsupial which are about the size of a rabbit and they are sort of bite sized. They're meal sized mammals which are very tame, very naive to the potentials of the predators which have been released in their land. And the plan has been to kill as many foxes and cats as possible. They do this using a poison called 1080, which is described by people who use it as a very effective and humane solution because it doesn't affect the native wildlife because they've got it. It's derived from a plant from Australia and so they've got their intolerances. But actually, when you read the descriptions of what it does to animals, it's horrifically cruel.

And I just add that into the book because I think it's really important that when you have your spreadsheet of whether you should act or not, whether you should kill or not, what tends not to be included in that spreadsheet is a column on cruelty and whether what you're doing is going to cause an enormous amount of suffering. But parking that to one side, what some people have discovered in Australia is that running alongside the control, the killing of the cats and the foxes, there's been a centuries long campaign against dingoes, the wild dogs that live there. And that's been principally driven by sheep farmers and massive efforts to kill these amazing animals off. And in one reserve where they didn't kill the dingoes, they found that the dingoes themselves kept the populations of foxes and cats to such a level that the marsupials were able to survive.

And so you end up having a sort of positive response to actually not killing. And I'm not suggesting in every situation around the world there will be an answer like this. But what I think would be lovely is for more effort to be put into looking to alternatives to killing.

[00:22:44] Speaker B: I think you have an example somewhere in there of efforts at biological controls but important animals to come and try and kill off the invasive species. And that doesn't seem to work very well. So I'm interested in also why the dingoes aren't going after marsupials.

[00:23:06] Speaker C: Well, I think what's happened, the marsupials and the dingoes have coexisted for hundreds and hundreds of years. Well, in fact, it's 5000 years, I think thousands.

[00:23:13] Speaker B: Millions. Yeah.

[00:23:14] Speaker C: Well, I know they've only been there for a few thousand years. They came over with people and so they've learned to coexist. And so I'm sure there is predation of the marsupials from the dingoes. I've not actually spent any time in Australia would love to, but those are species which have grown up together and found ways around this sort of thing. It's the new ones, the new predators, which have come in, which are really very efficient. And so the examples you alluding to bringing in one species to control another, is a famous story, actually, from Australia, where the cane beetle was causing havoc with the imported sugar cane being grown in Australia, and the chemicals weren't working. And so some bright spark had found the cane toad, which is large, bullfrog sized. Well, big, bigger than that, eats the cane beetle. And so they released them into Australia to control the cane beetle. But the cane toad took one look at Australia and said, yummy, and just went for it, and has caused absolute chaos all over the place, introducing species. I've been asked, how would you stop this? And I said, well, actually, a time machine is the only way. You go back in time and you just enact the sacred dictum, which is, don't be an idiot.

So don't release these animals in these places, please.

I mean, luckily now, certainly in the United Kingdom, there are laws which mean that you can't go and do as the postman did on North Ronaldy and release hedgehogs. It's against the law to do that on islands which don't have those species because of the chaos these things cause on a global scale. Obviously, that's never going to happen. And every enormous ship which ports, moves to another port, empties out the ballast water. We'll be bringing with it a whole host of species which are totally new to that environment. We are essentially recreating Pangaea, the supercontinent of millions of years ago, and creating a homogenous world where pretty much everything is the same everywhere, or that's what we risk happening.

[00:25:27] Speaker B: Yeah. Although I presume on Pangaea, there was some kind of ecological.

I don't want to say balance, because I know that's not a usable term in ecology anymore, but at least some sort of setup arrangement.

[00:25:47] Speaker C: Again, as I say, the time machine, be really good to go back and do some ecological studies. There certainly there wouldn't be any competition from other ecologists.

[00:25:56] Speaker B: No. But what if a human being, a pair of human beings, got loose?

[00:26:02] Speaker C: I think that would not be allowed.

[00:26:07] Speaker B: I'm sure that's been written about science.

[00:26:09] Speaker C: Fiction stories, but if not, I'm starting on this night.

[00:26:12] Speaker B: I want to get to the philosophical stuff. Okay, but before that, let's talk about. About owls. Do you know about the story of.

[00:26:21] Speaker C: The owls, the barred owls and the spotted owls? Yes.

[00:26:25] Speaker B: Yeah. Well, maybe you can explain that rather.

[00:26:28] Speaker C: Than I didn't go into it. I didn't go into it in the book because the story had been bubbling around for years and then I'd handed the book in and then suddenly it exploded again as a really big story. You'll have to remind me which species is the one which is being. Is the endangered species being. But basically what you've got is an issue of dilution.

[00:26:51] Speaker B: The barred owl is infringing on this northern spotted owl.

[00:26:55] Speaker C: So. Northern spotted owl, north.

[00:26:58] Speaker B: I don't think that they interbreed, but I could.

[00:27:00] Speaker C: Yeah, they do. Yep. That's part of the problem, is part of the threat is from dilution, but also what you've got is one of those situations and it's a bit like, actually with New Zealand. New Zealand, the invading, the invasive species are the. Blamed for the collapse in the native populations and they are very much part of that problem. But New Zealand is a massively degraded environment. It's just that we've been seduced by Lord of the Rings films into thinking New Zealand is perfect. In fact, New Zealand has been extracted in some form or other right from the very first humans being there. The very first Polynesians who arrived became the Maori, caused mass extinctions of species and on from there. And Europeans did a much better job, though.

We have created an environment which is very depleted. And so that is why the native species have a harder time being able to hang on in the face of being confronted by these invasive species. Now, for the northern species, you have.

[00:28:10] Speaker B: A case here of two native species. Right?

[00:28:12] Speaker C: Yeah. But what you've got is that the environment has already been massively degraded, so that there is. So this was a species already under systemic threat because they've had their wider environment damaged. It can be very easy then to focus all of the animus on the new species moving in to fill the niche which is being created by our stupidity.

Now, as to whether going and killing thousands and thousands and hundreds of thousands of. Of these beautiful owls to protect the other beautiful owls is a good thing, is another question, because it comes down to with what are you trying to achieve?

And it's something which I came across time and time again, is that you've got different approaches to these problems of an invasive species. You have people who look at control, which means essentially harvesting forever because you're controlling it year in, year out, and then you've got eradication. Now, obviously, for the barred owl, that's not going to work because it's a native species.

Whether a firebreak of some sort can be erected, who knows? I don't know enough about owl ecology, but I think the idea of beginning on a program which is going to result in, well, hundreds of thousands, maybe in the end, millions of owls, if it's going to be continued forever, that's what will be the result, being killed. Whether that can be justified is a really big question.

[00:29:45] Speaker B: Yeah, I mean, I don't know for certain, but my guess is a lot of time and capital was invested in protecting, trying to protect and sustain northern spotted owls. Right. And this is all being threatened. I mean, that was by fish and wildlife and other wildlife agencies, and it also had to do with. With logging, old growth logging back in the nineties.

But I don't know about that for certain. That's just my speculation.

When we come back, I'd like to talk about the ethical questions in terms of wildlife management and conservation.

You're listening to sustainability now. I'm Ronnie Lipschitz, and my guest today is you, Warwick from the UK, who has recently published Call of the Wild killing in the name of conservation. We've just been talking about the barred versus the spotted owls in northern California, where the US Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed shooting barred owls in order to basically sustain the population of northern spotted owls. Well, of course, this raises a whole set of questions which you address in the book, including should we play God?

So let's start with that. I mean, here we have a situation which was caused by human beings, by development act and extractive activities, and we're trying to. The wildlife service wants to somehow fix that. And I guess the question is, how do we decide what to do?

And should we just leave things alone?

[00:31:30] Speaker C: So, I mean, this is exactly where the book starts for me. In my head, it's like that idea of we should just let nature take its course. And then it was for me, that conversation. I spent a lot of time in my shed talking to myself, trying to work things through, and it was like, well, what? We're not leaving nature to take its course because the. The situation has been created by us. The idea of, should we play God or should we leave nature to take its course?

The latter part of that is just throwing your hands up into the air and saying, okay, Mother Nature, you deal with it. We messed up, but you deal with it. And all we're doing is heaping a whole bunch more work on the shoulders of an already rather embattled Mother Nature.

So therefore, that leaves us the uncomfortable choice of, okay, so we should intervene, we should do something, we should play God, if that's the best way of putting it. And in which case, do we have.

Now, in the book I write about, do we have a right to kill? What's interesting, I was very fortunate to do a literary a book festival platform and a radio program with Robin Wall Kimmerer, famous author of Brain Sweetgrass. And in braiding Sweetgrass, she talks about the rights, but she also talks about responsibilities. And I realized I'd missed a trick in cull of the wild by not actually investing in that analysis. Some of the thoughts that she presented from her culture about the responsibilities we have to try and redress to return things to some sort of balance.

[00:33:12] Speaker B: Well, go on. Go on.

[00:33:15] Speaker C: But that still leaves. Okay, so I think there is a very clear argument to say we should act.

Do we have then this right or responsibility to act in a way which kills some other creatures?

Throughout the book I made, well, initially it was an unconscious choice to identify animals as individuals and as sentient beings. I refer to who simply because it felt like the right thing to do.

These animals have rights. They have an amazing capacity to life. They can experience fear and joy, and they will protect their young. They will do their best to be able to sustain and look after their young. So all of these things are really crucial.

And I was then confronted with what turned out to be a very philosophical problem. And so I had to pull in help from cleverer people than myself. And fortunately, I mean, I live in Oxford, and this is a city filled with philosophers. And so I had walks with.

[00:34:26] Speaker B: What is the line? You throw a stick and hit a philosopher?

[00:34:30] Speaker C: Pretty much. So it is a. So, I mean, it's very fortunate. And so, I mean, I'm walking in the park with various philosophers having cups of tea, and I was being presented with, when I put out the practical issues I was confronting. And they say, well, this is a very clear difference between. And this is a word which I now use correctly, deontological thought or normative thinking, the idea that something is right or wrong versus utilitarian thinking, which is, is it good or bad? Basically. And I found this utterly fascinating. Now, obviously, what I was doing was getting 101 in philosophy on a walk around the park, and I am very, very much not a philosopher. However, what I recognize is that the normative point of view, the right versus wrong, isn't tenable if we are going to accept that we have already upset a system and we should act to try and fix it.

I spent time with my friends, who are activists in the animal rights world, trying to get them to answer the question of what would you do in these circumstances? And it was a really interesting exercise. I couldn't get a good answer. So I recognized from my own perspective, I am what one would describe as a utilitarian. I'm trying to minimize harm and maximize good.

And that is, yeah, I would. Oh, I would love to go back and spend five years of my life learning about philosophy. It was fascinating stuff. I don't have time, but it was a really good sort of beginning of forcing me to think a little bit smarter about what I was being confronted with.

[00:36:18] Speaker B: I have to say that, you know, learning about these, the philosophical nature of making choices, you know, is really interesting, but then you have to act and you can justify deontology versus utilitarianism, but at the end of the day, you either do something or you don't do something. And so the question that we come back to is, what is our responsibility and obligation to do something?

And I wanted to say one other thing about that, which is, of course, there is a history, there is a human history of depredation, not only on animals, but also on other human beings.

And then there's evolution with its operation. It operates on individuals, but it affects species largely.

These are getting back to this question of, of deontology versus utilitarianism. Neither of them really, I think, addresses this question of historical obligations.

And is that something that you've, I can't remember if you wrote about in the book or is that something you've thought about?

[00:37:41] Speaker C: Well, I mean, part of it. I mean, I do talk about this, the deeper history of these things, simply with the question of what are we trying to achieve?

[00:37:49] Speaker B: Yeah, right.

[00:37:49] Speaker C: Because that is something which certainly in the United Kingdom, 10,000 years ago or so, we split off from mainland Europe with the rise of waters as the glaciers retreated and the ice age ended. That created an island and that created a fairly sort of clear system. And gradually species moved in.

They could cross over from Dogland. And we managed. Then we got people moving on into the United Kingdom and.

But at which point are we trying to draw the line? Where are we saying is the prelapse area in idyll that we are striving for neolithic farmers? Did they really? Well, they did help destroy a lot of the forestry, but we can't go back to the neolithic farms. That's ridiculous, because we've got the rabbits, which the norm has produced, or the door mite edible dormice. Half our deer species are invasive deer species. So much of the United Kingdom's wildlife could fall under the category of an invasive species, even the hare, which we consider to be such a seminal part of our folklore and mythology. I mean, the mountain hare is native, but the brown hair isn't.

So where do we draw the line? And I think that idea of drawing a line is a nonsense because what would. It is simply physically impossible to do that sort of thing. It's a case of looking at can we fix a problem? Rather than can we create, as I say, this prelapsarian idyll?

So I'm very conscious that that is something which tends to get. These things get conflated. The plan. In the United Kingdom, we've got american gray squirrels wiping out native red squirrels. And it used to be thought that was just down to competition. But actually the gray squirrels carry squirrel pox virus, which they're immune to, but the reds die horribly from it. There are people wanting to keep on killing gray squirrels to protect red squirrels, but that means, as I mentioned earlier, that's the idea of control. And it goes on, and it's just harvesting gray squirrels and it means it goes on forever. I see a real value in having islands which are protected. So Anglesey is an island off north Wales where one man is responsible for killing 7000 gray squirrels and re importing red squirrels. And now they flourish there. So I suppose for me the question is, what are we trying to achieve?

Is it going to be just this constant battle of control, or can we eradicate a species and turn back, at least in an area, a clock, so that we don't have that particular problem?

[00:40:35] Speaker B: Yeah, well, I mean, that raises the issue of protected areas in various parts of the world, right? And the presence of human humans within or without which we're not going to talk about today.

That's a complete, you know, that's a.

[00:40:55] Speaker C: Story I just should point out. When I started writing that, I wrote a small chapter, a mini chapter on fortress conservation. And as I was writing it, I was so furious, so angry, and I was just like, I've got to write a book about this. And then afterwards realizing it would be such a miserable, miserable book to write, and I need to write something happier, at least first.

[00:41:20] Speaker B: Well, I mean, the book has been written several times, not to burnish my credentials, but I was the editor of a book about 25 years ago in which one of the contributors wrote about coercing conservation, which was exactly about this question of people living inside of conservation zones, what are their rights?

And of course, it's the basis of a lot of activism by indigenous groups around the world. So basically, what you're telling us is that rather than trying to identify this prelapsarian date. Right. Which is always a question with conservation biology, I think it's more looking at a problem and deciding whether or not the problem defined by us, of course, as a problem needs to be addressed.

Is that a fair statement?

[00:42:20] Speaker C: Completely.

I had hoped, naively, when I started writing color of the wild, that I would come away from it with a straightforward answer, a manifesto, simply explaining what needs to be done.

But what clearly is the answer is that everything needs to be looked at individually, and it needs to be assessed closely to see whether it meets a set of questions which really, I feel needs to be met before it can be justified. And I explored this with different organizations, different academics as to what they considered to be the necessities to enable these things to happen. And only one of them introduced, as I mentioned earlier, the issue of cruelty, for example, which I think is something which is it becomes. It's where my rigorous scientific head, well, not so, gets deeply slapped around the face by my quite prodigious heart. And just saying, you cannot just ignore this.

And if you're looking at the. In the great scheme of things, the millions of rodents which are killed in a horrible, horrible way using anticoagulant poisons, that is something which has to weigh on the shoulders of anybody who is making the decision that this is a choice that they should take, in the same way that the choice not to act will also result in death and will also result in misery.

Both of these choices, in action or action, result in death.

And this has to be considered by the people who are making the decisions.

[00:44:07] Speaker B: You're listening to sustainability now. I'm Ronnie Lipschitz, and my guest today is Hugh Warwick. And we've been talking about the ethics of conservation management, which involves culling or killing certain species that are invasive or intruding on the territories of endangered species.

And the question is, really, what sort of consideration should animals get?

And you start the book out with the discussion of exceptionalism and speciesism, which we haven't talked about, but which I think is maybe for the last segment of the show, is an interesting topic. You've also mentioned the rights of nature, and I've had a couple of shows about the rights of nature, but not quite in this sort of terminology.

Do you have any kind of thoughts about this concept of rights of nature and rights of, you might say, species?

[00:45:12] Speaker C: I think it's going to require a lot of philosophical effort and thought, a lot of ethical effort and thought to try and formulate things. I know there are people working on it, for example, looking at the rights of a mountain, the rights of a watershed, and granting these things personhood. It's been tried with the non human great Ape project, looking at granting rights to the great apes. And so in colours of art, I look at this idea. I mean, it was a fascinating exercise for me to go back to my teenage reading. And it was soon after I became aware of the issues impacting on animals that Peter Singer's seminal book, Animal Liberation, came out. And I remember reading, I mean, I looked at the words in that I don't think I really understood very clearly what was going on. All I felt was, here's somebody who's saying in really complicated language, stuff that I think agrees with how I feel, but even then, I didn't really get it, but in that these ideas of human exceptionalism, of speciesism, are brought up. And for me, as a naive teenager, this was really eye opening. And it was that idea that we, homo sapiens, are exceptional. We are exceptional purely by luck. So there is no special thing that grants us this exceptionalism. We are better at many things than other species, but vast numbers of other species are far better at stuff than we are. So let's not. We're only measuring it. I don't know if you remember, there's a cartoon of a. I know, a monkey, a fish, a snake and an elephant in front of a board. And they say, right, let's judge who is the best. First one up the tree is the winner. And it's just, you can't measure the quality by using this metric, which only applies to humanity. In fact, I'm so bold as to suggest a new name for homo sapiens. Anyway, in the book, because of reading so many depressing stories about what we humans have done to the natural world, I was left with the conclusion that we should possibly rename ourselves as homo ochisaur, which is not man the wise Homo sapiens, but homo man the killer, which does seem to be rather more appropriate.

We are exceptional at many things, but we are not exceptionally exceptional. And every time we try and assert human exceptionalism because we do this, somebody finds an animal that can do it, whether it is from Jane Goodall's work exploring tool use amongst the chimpanzees in Gombe. And it was repeated on the west coast, the west side of Africa as well.

The crows, using tools, octopuses, they're not even vertebrates, and they do things that we can only dream of. So I don't stand and say animals have an absolute right to be untouched, because I believe that. That we can't hold that deontological point of view, but I believe we must consider the individual nature of the animals, that we are engaged within this problem, and we must consider them as agents, as individuals who've got the capacity to suffer. And that we should be very cognizant of the fact that this is taking place within an ecosystem which itself we may be trying to re engineer into something which we want, rather than is necessarily something which the ecosystem itself. Well, I can't really say want because I'm not sure of the consciousness of an ecosystem, but that idea that if it was to be self willed, where would it go?

And it may well be somewhat very different to what we're trying to force it into because we've only got our limited and blinkered view of what an ecosystem may be.

[00:49:15] Speaker B: Yeah. I want to actually challenge you on one point, that humans are exceptional in the respect that they are concerned about such things.

[00:49:25] Speaker C: Okay.

[00:49:26] Speaker B: And I mean, in a sense, our conscience, I suppose, is the greatest challenge with respect to, you know, what should we do and what should we not do? And I'm not sure that's an advantage.

[00:49:45] Speaker C: In any sense, but did read somewhere somebody saying that the greatest disaster of evolution was consciousness, because from that comes awareness of mortality, and from that comes the necessity of inventing a God, and therefore you're doomed.

[00:50:01] Speaker B: Yeah. One of my recent guests talked about the. The fear of death as a motivator of all sorts of violence against others and against nature.

So we're getting close to the end of our time together, and I'm just wondering, what do you have planned for the rest of your life or the next couple of years?

[00:50:31] Speaker C: Are you suggesting those two are equivalent? Because that's rough.

[00:50:34] Speaker B: I'm not, of course.

[00:50:38] Speaker C: I have two books to finish this year, one on bats and one on nocturnal nature. They're small little things for a small publisher in Wales.

And I have a real desire to write a book about something which causes fewer tears. Really, I'd like something. So I'm exploring a book which is going to be happier and is going to hopefully infect people with a newfound love of the natural world.

But also writing books does not make a living. And so I have to carry on doing the sorts of many, many other day jobs that keep me going. So, yeah, the next few years, hopefully new book commissions and, oh, hopefully actually, in the next few months, hopefully I will be going to an awards ceremony. Cull of the Wild has just been nominated for a very prestigious literary award, which I'm really, really excited about, the Wainwright Prize.

So that is short term thinking. That'll be sometime in October, November. I'll find out about that. But I only found out yesterday that I got the nomination through. So that is. Yeah, that's a good step.

[00:51:57] Speaker B: Yeah. I mean, generally speaking, what's been the reception? I mean, I'm sure that I read Elizabeth Kolbert's piece in the New Yorker, but, you know, have you found that people are, reviewers are being critical of your position or supportive? I'm just curious what the reception amongst book reviewers and maybe amongst ecologists, I don't know.

[00:52:23] Speaker C: Okay. That's really interesting. When I first pitched the idea to Bloomsbury, they were very, they actually took it to an extra layer, a sort of security layer to worry about threats to myself for stepping into this sort of territory and also their reputation.

My biggest fear was the extreme points of view. So those who take great pleasure from killing, which is something I really struggle with, we didn't get on to talk about that, which is, for me, is quite important, is the motive behind the killing and those who take great, great, great, very hard stance against any killing at all.

And so I was worried about those two voices. And I had a moment a few weeks ago on Twitter. I had a hunter get in touch and post a tweet about the book. We had an exchange. He ended up saying, I disagree with some of what's in the book, but I think everyone should read it. And the very following day, unrelated, I had a tweet from the Hunt Saboteurs association, the chair of the Hunt Saboteurs association, who are animal rights group in the United Kingdom, saying that they thought I was a bit mean to the animal rights lot in the book. We took it offline, we chatted about it, and he ended up tweeting almost the same words. I disagree with some of what's in this book, but I think everybody should read it because what I, I deliberately didn't spend a lot of time with very angry animal rights activists and with very gun happy gamekeepers and hunters because they are the extreme voices. I believe that most people, and going back to what you said right at the beginning, about the only thing being in the middle of the road is roadkill. Most people actually have a more moderate view of these things. And, in fact, I end the book by looking at one of our former politician in the United Kingdom called Rory Stewart, who happens to be rather wise. And he talks about, he did a program for the BBC about argument and debate. And he talks about how political discourse used to be distributed pretty much like a bell curve, a normal distribution curve with small numbers of extreme views on either end, but most people being somewhere in the middle. And that with the rise of social media, that has been turned into an empty wine glass and it's empty in the middle because people have been cowed into silence because of the fear of being shouted at by either side, or they've been drawn towards stronger feelings. I did begin the book wondering about taking a side in this because it would be much easier to have a side and to have allies, but actually recognize that the most honest thing to do was just to use my own naive, bumbling path through it. I operate like a hedgehog. Follow my nose and, and just see where that leads me. But also to listen. And listen and listen, because most people, when you get them outside of their bubbles and the lensing effect that those bubbles have, most people agree about most things. They'll find some bits which they really disagree with. You know, one gamekeeper I spoke to, we actually disagreed most about who had recorded the best versions of Sibelius's Fifth Symphony, but we also disagreed about getting joy out of killing animals.

But we actually, the, most of the body of our conversation was about our shared love of nature. And that's what I really want to get over, is we can have conversations with people we disagree with, and the only way we're going to make progress. There's a quote from Joseph Joubert in the book, which was the point of argument is not winning, but progress. And I actually want us to move forwards in this where we can then actually confront the really enormous challenges that wildlife managers, conservationists face without the rancor which can arise.

[00:56:19] Speaker B: Well, that seems like a good point on which to end. So you, Warwick, thank you so much for being my guest on sustainability now.

[00:56:26] Speaker C: An absolute pleasure.

[00:56:28] Speaker B: You've been listening to a sustainability now interview with Hugh Warwick, spokesperson for the British Hedgehog Protection Society and author of Cull of the killing in the name of conservation.

If you'd like to listen to previous shows, you can find

[email protected] sustainabilitynow and Spotify YouTube and Pocketcasts, among other podcast sites. So thanks for listening and thanks to all the staff and volunteers who make KSQid your community radio station and keep it going.

And so until next, every other Sunday. Sustainability now.

[00:57:10] Speaker A: Good planets are hard to find now. Temperate zones and tropic climbs and run through currents and thriving seas, winds blowing through breathing trees, strongholds on safe sunshine.

Good planets are hard to find.

Good plan.