Episode Transcript

[00:00:08] Speaker A: Good planets are hard to find Now.

Temperate zones and tropic climbs and run through currents and thriving seas, Winds blowing through breathing trees, strong ozone and safe sunshine.

Good planets are hard to find. Yeah.

[00:00:36] Speaker B: Hello K SQUID listeners. It's every other Sunday again and you're listening to Sustainability Now, a bi weekly case Good radio show focused on environment, sustainability and social justice in the Monterey Bay region, California and the world. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschitz. As the recent deadly floods in Central Texas remind us, nature bastards, Bats last Floods have been much in the news in recent weeks. Around the world, there seem to be a growing number of severe weather related disasters that kill many people and lay waste to towns and communities. In fact, floods seem to be happening perpetually and everywhere. We call these natural disasters, but they're better understood as planning disasters since cities, towns and other sites of human occupation are often placed in river plug flames, river floodplains, or places with a history of flooding.

But what happens after the floods as communities make plans to repair the damages?

Why does rebuilding often become the trigger of intense and extended political and social struggle, sometimes lasting many years? Dr. Ken Konka, emeritus Professor of Environment, Development and Health at American University in Washington D.C. decided to follow the planning process in a flood prone town in which he lived.

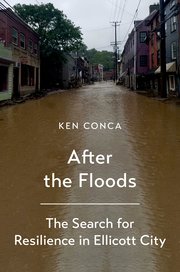

He's just published after the Floods the Search for Resilience in Ellicott City, a study that offers a blow by blow account of these struggles and elucidates his explanation for why they arise and persist long after the water has vanished.

Professor Ken Kankonka, welcome to Sustainability Now.

[00:02:15] Speaker C: Thanks Ronnie. It's great to be here.

[00:02:17] Speaker B: So why don't we start with you telling us who you are and what your background is?

[00:02:24] Speaker C: Sure, that could be a long story.

I'm a professor. I teach in the School of International Service at American University. I'm in a department called the Department of Environment, Development and Health. So it's a very interdisciplinary orientation.

I grew up in Providence, Rhode Island.

I'm from a working class family.

I completely intended to be a government bureaucrat because in my experience, the sort of fdr, Hubert Humphrey, New Deal Coalition, labor union background that I had, government was actually a very positive force in my life for many years. And so I went to college. I was a geology major because I was encouraged to go into the sciences. I segued into an interdisciplinary master's program in environmental policy. And then I moved to Washington D.C. fully intending to make a career there.

After two years there I. I realized that I was not cut out for government work that I felt the government at the time was kind of brain dead and not interested in ideas, which I was always interested in.

Ronald Reagan had just been elected for his second term, and the administration was pretty hostile to most of the things that I thought were important.

Imagine such a scenario if you can.

So I went to Berkeley and enrolled in an interdisciplinary program to get a PhD.

I never intended to be a professor, but at the end of my time there, I was running out of funding and I needed health insurance. And so I went over to the Peace Studies program and I said, hey, how about if I teach a course about environment, peace and conflict? And I taught that in 1990, just as the first Gulf War, Bush, the Elders Gulf War was kicking off. And so we were immediately thrown out onto the lawn because the radical Berkeley graduate students were boycotting classes and we were doing teach ins, no blood for oil, et cetera, et cetera. And that was such a heady moment for me that I realized that what I really wanted to do was be a college professor. And. And I have been for some 35 years now.

My work and my teaching, my research and my teaching focus mostly on two or three different areas. I do a lot of work on water, as we'll be discussing throughout this conversation.

I also do a lot of work on the relationships between environmental change and processes of violence, peace, and conflict. We know there are lots of tensions, but we also know there's lots of cooperative potential and lots of peace building potential around our shared ecosystems and our shared environmental identities and our shared needs around the environment. So do a lot of work in that space.

And I've also done a lot of work on global institutions focused on the UN quite a bit. I've worked with the UN Environment Program, but I've also studied the UN in a pretty critical capacity and trying to understand why global institutions so often are ineffective in dealing with some of our planetary challenges. So that's me.

[00:05:21] Speaker B: So you've done a lot of work on water, and I'm curious, why did you decide to focus on water? And what sorts of topics have you addressed within that particular remit?

[00:05:36] Speaker C: Sure.

So, I mean, the simple answer to that is that water flows, and because it flows, it challenges so much of what we think we know about politics, about property, about institutions, about communities.

I was in an interdisciplinary program, but I always had an interest in political science. Frameworks of international relations and concepts of institutionalization, concepts of global governance, concepts of sovereignty.

And I always found the idea of sovereignty pretty problematic. Right. It was based on the idea that things will Sit still for governance, highly territorial. There's a territory and there's a people, and they're wrapped in some sort of a bundled blanket of rights and privileges and autonomy that we call sovereignty from a sort of a legal, institutional perspective.

And that, you know, maybe that's true of Norway or Sweden, I don't know. But for most of the things we call countries in the. In the world, that's a really polite fiction compared to what's actually happening, where all sorts of goods and bads are going kind of screaming across borders. Knowledge moves, people moves, money moves, pollution moves, violence moves. And so when I was coming up, you and I are contemporaries. And when I was coming up as a graduate student all those years ago, these new ideas about globalization and the problematization of sovereignty were very popular at the time. It was just sort of a new notion for some people at least.

And so as someone who was very interested in global environmental challenges, water struck me as something that was particularly illustrative of a lot of those.

A lot of the ways in which the actual ecology, the actual environment that we live in is a bad fit with some of those designs for making life sit still for governance.

So whether it's sovereignty, whether it's property rights, whether it's community, whether it's identity, those have always been the things that have most interested me about water.

The other thing is water is absolutely essential, right?

It's the lifeblood of ecosystems.

It's a basic human need.

It should be a human right, although that's often observed in the breach.

Water is the delivery mechanism of climate change. We're not going to walk outside on a Tuesday afternoon and smack ourselves in the temple and say, good God. I just noticed that it's 3 or 4 degrees Celsius, global average temperature warmer today, the way most people actually experience climate change. And we just had a tragic illustration of this in Central Texas, right Is through changes in rainfall patterns, flooding, droughts, changes in agriculture, through soil moisture, et cetera. So I got started being interested in water because it's kind of an interesting intellectual puzzle, but it's also got this enormous consequential character.

When I first started doing this, I was approached by a senior colleague, someone I very much respected, at a conference, I don't remember, workshop, conference, something. And she said to me, I hear that you're getting interested in water.

And I said, yeah, that's true. And I explained a little bit about why. And she said, don't.

And I said, why not?

And she said, because it's so damn interesting. That once you get in, you'll never get out again and you're going to have to make a career of it. And that was absolutely the case. Yeah. Several books later and whatnot, that was absolutely the case.

[00:09:29] Speaker B: Someone I remember said water is intensely political and there's this sort of ongoing effort to depoliticize water. I mean, again, we saw this in the case of Central Texas, right. The, the, the fights over the politics of water and not using politics to, to talk about the floods.

And you know, I, I don't know if you have any thoughts about that idea, the depoliticization of water as a, you know, something that people not necessarily fight over but struggle over.

And yet that never happens, the depoliticization.

[00:10:10] Speaker C: Sure. I mean, you know, water's intensely political.

You know, My latest book, which we'll chat about a bit in this hour, is about flood risk in a small community that suffered two fatal flash floods within the space of 22 months, each of which was based on an allegedly one in a thousand years probability rainfall event 22 months less than two years apart.

And what I'm trying to do in that book is essentially trace what you just suggested, all of the ways in which these are intensely political decisions and that we need to treat them as such.

Part of that stems from the fact that that was already mentioned, that water doesn't easily sit still for governance. It flows. Right. The economist will tell you it's difficult to establish property rights in water and in our system.

Vital resources around which it is very challenging to establish property rights become exceedingly contentious political controversies. Look at the situation around the Colorado river, which I'm sure many of your listeners are familiar with today, and you should get someone on at some point to talk about that because it's quite a tale.

Another reason why it's intensely political is because of the enormous distributive consequences. You know, it's interesting around floods and disasters, these used to be referred to as natural disasters. But if you talk to anybody who works professionally or is an activist or what have you around disasters, they have banished the word natural from their vocabularies. Right. And as we saw in Central Texas, you know, there are some natural elements to what happened there, and we can chat about that if you'd like.

But there's also distributive consequences because of the way we practice our politics, because of our economics, because of our social institutions, because of the way people are distributed unequally across the land, the landscape, and, and, you know, some have no choice but to be in the floodplain and, and, and, and so on. And so I, I think it's obvious that there are distributive consequences to disasters and that's why we've banished the word natural. They're not natural, they're socially constructed phenomena. Some people are in a much greater position of vulnerability than others.

But one of the things I tried to stress in the book is it's not just the consequences of the disaster. The planning and preparation and prevention efforts are also intensely political. And there are winners and losers that are generated by those efforts.

The recovery processes are intensely political and favor some over others, so on. And so one of the things that we need to do is sort of puncture this myth that we're all in this together.

You know, environmentalists like to say there's no hiding from climate change and it's going to affect rich and poor alike and so on. And in the long run that's true. But of course, as John Maynard Keynes famously said, in the long run we're all dead. And in the short run, some are much more vulnerable than others, some benefit much more than others, whether we're talking about preventive efforts before, immediate response efforts during or recovery efforts afterwards. And so that's some of what I was trying to capture. If you think about water and you think about what is the world of water going to look like 30 or 40 years from now, I think it's actually fairly predictable. I think it's pretty clear that we're going to be storing more water to smooth out the unevenness that climate change is imposing. The extremes of flooding and drought and so on, we're going to be recycling more water because the idea of putting 6 gallons of water in my toilet, right, cleaning it to a world class standard, using as much energy as we use in the mass transit system of a typical city to clean and pump that water, pumping it to my toilet, using it to flush away a few ounces of urine, cleaning it again to an environmentally acceptable discharge standard, and then just dumping it in a river.

That's madness, right? So we will be recycling more water, we'll be pricing water differently to recognize its scarcity value, and we'll be designing our landscapes to be more resilient to flooding and drought. Those are all good steps. Those are all things we absolutely have to do.

But the fact is there are enormous distributive consequences around each of them, right? We know from the history of large dams that there are losers, that they can be ecological and human rights nightmares.

So we have to do this in an equitable manner. We know that when you recycle water, there's someone using water downstream as a livelihood resource, even if it's dirty water, even if it's polluted water. And so if you close that loop and recycle the water, that may make sense ecologically and economically, but it's also a massive reallocation of resources from one group of people to another group of people. And in the flood story, the redesign of the landscapes obviously is intensely political. Who has to move to make room for the river? What community gets shattered to make room for the river?

[00:15:34] Speaker B: You're listening to Sustainability Now. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschitz. My guest today is professor emeritus Professor Ken Kanka, who has just published a book called after the Floods the Search for Resilience in Ellicott City, which is in Maryland.

And we'll talk a little bit more about Ellicott City in a moment. We've just been really talking about the distributional consequences of managing water and flood risks. And I just wanted to make the comment that usually the distributional consequences of benefit those who have capital as opposed to those who don't, who are usually left high and dry. Does it, so to speak.

Well, you know, you use the term. I was going to quote at you, but you use the term managing flood risk remains intensely political.

What exactly do we mean by flood risk? And you know, you can use these, these recent events as well as a way of illustrating that.

[00:16:35] Speaker C: Sure. So let's talk about Central Texas, because that's ripped from the headlines and obviously a really scarring and traumatic experience, obviously for the people who experienced it, but for much wider circles and in some ways for all of us, you can't read the accounts of what happened and not in some sense be scarred by it.

Why did flooding occur in this place at this time?

Rivers flood, right? It's what they do. It's their job ecologically.

And in many ways, some of the challenges or flooding are tied to the way that we would like to be able to live in certain spaces, as opposed to the way that the geography, the terrain, the geology, the hydrology of the space is adapted. So there's always going to be some degree of risk if you're in low lying areas, if you're in the floodplain, if you're in the vicinity of rivers, if you're along a coast that is prone to storms and hurricanes, typhoons and whatnot. But there's a lot more to that story than just that.

Climate change is obviously a piece of this, but exactly how.

There's a few different mechanisms that are at work. One is that a warmer Gulf of Mexico, forgive me for still calling it the Gulf of Mexico, generates more intense and more frequent storms. The science of that is still coming together, but we have a reasonably good understanding. And that was the case here.

It was also, as storms that move over the land and drop vast amounts of rain go, it was also a relatively slow moving storm and that triggered a lot of rain. In this case.

We know that that may in fact also be a piece of the climate change equation.

Some places are going to get wetter and some places are going to get drier as a result of a changing climate. And the very simple broad brush bumper sticker answer is the wet are going to get wetter and the dry are going to get drier in many parts of the world. Not always, but in many parts of the world.

But the other thing that we know is that a wetter, you know, moister, a warmer and therefore more moist atmosphere is going to deliver however much rain, it does deliver in bigger and more intense storms. And we've got a pretty good meteorologic record now of some decades showing that that is in fact happening. However much rainfall you're getting, it's coming in more intense storms. So where I live in the mid Atlantic east coast of the United States, we've seen a 70% increase in precipitation over the last few decades. And we've seen this pattern that for that amount of precipitation, we see it coming in more intensive storms, and that's what happened here as well. The landscape that that slow moving storm dropped a vast amount of rain onto in a very short period of time was not as well adapted to manage it as some others. Just in terms of the natural features, right.

The composition of the soils were thin and their composition was such that they didn't absorb as much water. The morphology of the landscape just kind of did what nature does. It funneled the water toward the rivers, which then aggregate it. But there's a human side to this story as well. There's a political and institutional side to this story as well. When we talk about the risk, all of the things I've said thus far are kind of baseline risk factors, some of which we're making worse by where we choose to build buildings, by how quickly we choose to change the climate, et cetera. There was quite a bit of building in the floodplain in this area, right. Including these summer camps that have been sort of the focal point for media attention. And the focal point for the tragedy because of the large number of children that died in the storm.

You know, it wasn't a good place to put those camps. There has been a lot of progress with, in many parts of the United States in not building in floodplains. More and more, county level governments, city level governments are starting to recognize this as a very dangerous and costly problem. And so there's been quite a bit of progress with that.

But, you know, there's always been good reasons to want to live down by the river.

And we'll see that in the case of Ellicott City when we get there.

And so the fact that people were in the floodplain, you know, enhanced the risk as well. And that leads us to what could be a very long conversation about, you know, the national insurance programs and the way that, you know, we create incentives for people to rebuild in spaces that are very, very dangerous. And I understand why they might want to rebuild there. That's community, that's identity, that's ties to the land. I'm not going to dismiss that out of hand. But if you look at the National Flood Insurance Program, one of the things that you see is this is about 25 or 30,000 properties that are serial repeaters. They keep getting rebuilt and keep cashing in on the National Flood Insurance Program. So some of this is the geology, the morphology, the hydrology, but some of this is the incentive structure that's. That's been created.

We also can't leave this without talking about the assault on government and bureaucracy that the Trump administration has been carrying out since the beginning of this year. And that story is going to take a while to tell, but accounts are starting to leak out about how cuts in the national oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, cuts in the National Weather Service, compromised the ability to get the warning out in the most effective manner and compromised the planning and funding for some emergency response mechanisms that some people in this space had been calling for for a long time.

The probably the most poignant thing about that, the thing that struck me the most, is in the context of some of the campers that, that were swept away and were killed, this came in the middle of the night.

You know, it was not, you know, it was almost a sort of a perfect storm of difficulties in some ways. But, you know, there were kids at that camp in a different bunkhouse just a quarter of a mile away and a little bit up the watershed that survived.

And so, you know, this. This wasn't. Oh, we were just overwhelmed, and this was inevitable. And there was. There was nothing that could be done slightly quicker, slightly more effective warning systems, slightly more careful planning around evacuation and around where we put these campers. And watching the rain and. Etc, probably could have saved them. Yeah.

[00:23:58] Speaker B: I just want to mention that I actually went to summer camp in that exact space 60 years ago.

[00:24:04] Speaker C: Oh, my goodness.

Wow.

[00:24:06] Speaker B: Well, let's talk about Ellicott City. All right.

And what happened there. First of all, why Ellicott City? You know, what motivated you to do this project and this book?

[00:24:19] Speaker C: Well, the first thing I have to say is it's not Ellicott, although it looks like that. It looks like it rhymes with Epcot.

It's Ellicott.

And as people like to say.

[00:24:29] Speaker B: I'm sorry, I'm sorry, all my listeners.

Not going to go change this.

[00:24:33] Speaker C: No. And that's fine. I bring it up. I bring it up for a reason. You know, people, it's. People say Ellicott rhymes with delicate.

And if you say Ellicott, you're not from here.

[00:24:45] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:24:45] Speaker C: But the question of who is from here, the question of who speaks for Ellicott City in the conundrum of what to do about its flood risk is a very, very complicated one.

Ellicott city is a 250-year-old mill town in central Maryland. It's positioned in between Baltimore and D.C.

it used to be a chartered incorporated town, but it lost its charter during Prohibition. It was the only wet town in a dry county, so it was the only place that you could buy alcohol. And so I was looking at some survey data from the turn of the millennium into the 20th century. And there's a barrel manufacturer, and there's a hardware store and there's a grocery store, and there's 12 bars and liquor stores.

But when Prohibition put a stop to all of that and cut off all of the tax revenue, the city went bankrupt. And they tried to implement an income tax, but the good citizens of Ellicott City weren't having that. And so the state had no choice but to strip it of its charter and it got folded back into Howard County.

Most of the space in the state of Maryland is not incorporated into cities and towns. The county is the lowest level of analysis. So Ellicott City is a fascinating and distinct place. It's got a really fierce identity.

It's got a very long history.

It's one of the jewels in the crown of east coast historic preservation. The National Road, the first highway in the United States, goes right through Main Street. There's some amazing preservation of structures. The first railroad station in the United States, the B&O Railroad, the first depot connected Ellicott City to Baltimore. If you know the probably apocryphal story about Tom Thumb the steam engine and the race between the steam engine and a horse drawn buggy, it's not clear whether that ever actually happened. But if it did, it happened on the stretch between Baltimore, an Ellicott City.

[00:26:53] Speaker B: I just want to intervene again. B and O is one of the four railroads in Monopoly, isn't it?

[00:26:58] Speaker C: That's exactly right. That's exactly right.

[00:26:59] Speaker B: Go on.

[00:27:01] Speaker C: And the reason that the railroad started in Baltimore and the reason that Ellicott City exists is a group of Quaker brothers moved down from Pennsylvania and decided to try to convert the farmers of that part of central Maryland from growing tobacco based on slave labor, which is what they were doing, enslaved people's labor, which is what they were doing at the time, to convert to wheat and to convert to wheat for export. And that required a whole infrastructure, including a mill, to grind the wheat into flour so that it could then be shipped by this rail line into Baltimore and sent to Europe or other parts along the east coast and so on and so forth. And so a town sprung up. It's got a very long history of flooding.

There's 30 something episodes that are identified by the local historical society.

There's an 1868 edition of Harper's Magazine for which the floods in Ellicott City were the COVID story. And there's an absolutely horrific and frankly, a little bit lurid account of floods coming downstream from up the watershed and other parts of Maryland, you know, dozens of miles away.

The river there, the Patapsco river, drains a large swath of central Maryland on a bright sunny day and dozens of people being killed. And people had the habit when there was a river flood of climbing onto the roof of their house. But this flood was so big that it just swept the houses away. And so people on the banks had this horrific experience of watching their neighbors be carried off to their death clinging to the roofs of their houses. There's a story that I couldn't completely verify, but I believe it, that the mayor.

There was a flood in 1866 and another in 1868. Again two huge floods two years apart. What's going on here?

The mayor owned a lumber yard down by the river and it was swept away in the 1866 flood. He was offered a nice stone building up the hill, safe from flooding, if he would throw the next election to the opposition. And apparently the mayor agreed and took the building and tossed the election. It's a Very colorful history here around flooding. I wrote this book about this town for a few reasons.

First, there were two floods. And this is our future, right? We have a lot of one off accounts, right? Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, Harvey in Houston, et cetera, et cetera. Most of them are single shot episodes in big cities that are in the spotlight and that can tap substantial resources, whether it's for flood prevention or for flood recovery. This is a small town that got kicked in the teeth twice in a very short period of time. That's the kind of process in politics we need to understand better, because that's the future for small towns in the United States and around the world. Second, it's an affluent community that seemingly has every advantage in the face of this challenge. It's a progressive community. Planning is not a dirty word. Climate change is not a dirty word. It's an affluent community. Howard county, with Ellicott City being one little corner of the county, is the sixth richest county in per capita, per capita measure in, in the United States. And that's not because there's some millionaire mile, it's because lots of doctors and lawyers and college professors, including this college professor who lived there for 14 years and lived through the first flood.

The first of the ones that's in the book split the difference between Baltimore and Washington for, you know, two earner, upwardly mobile, upper middle class families and so on.

There's also a fierce civic identity in this place because of the history, because of the culture, because it's got that small town feel to it.

So when I started this project, I thought if ever there was a place that could navigate this vexing challenge of how do we live resiliently in a flood prone watershed, this town might be the place. And so after the first flood, when the county launched a very ambitious master planning exercise for watershed resilience, I started going to the meetings. I lived in this town for 14 years. I raised my kids there. I had water in my basement that night in 2016. Now, to be clear, I didn't live in the most flood risk part of the town. I lived about four miles to the west on converted farmland. But you know, I used to hold my office hours in a coffee shop down on Main street that got destroyed in the flood. My wife and I used to dine down there all the time in a restaurant we loved, had a little piano bar and whatnot that got destroyed in the flood. So on one level, I was intimately familiar with this. And I had started going to the master planning meetings because I thought it Was an interesting experiment.

Then the second flood came and the wheels came off, and these really extreme politicized solutions started to emerge.

Solutions in air quotes. Tear down half of the historic district. Well, not having this debate about how much, you know, was actually in danger, but tear down a large swath of the historic district to make room for the floodwaters? No, the problem is development up in the hills around, because this is a flash flood. The water came down from the hills, it didn't come up from the river. And there's been a lot of housing constructed. And so many people feel like Ellicott City. The historic district now sits at the bottom of a concrete funnel that's been created by housing developments. So banned development in the watershed was another popular Solution.

Build a $150 million. Well, nobody really knows what it's going to cost. $150 million. Tunnel over a mile in length under the town to make room to carry the flood waters under and around the town entirely. So I started out thinking, you know, I'm a citizen of this town. I have interests. I own property. Let me see what's happening. This could be a really interesting experiment to realizing that this was a cautionary tale, that this town, with every advantage, was nonetheless dragged through a bitterly conflictive process about how to respond to this.

So I wrote it for those reasons, and I wrote it because I lived there.

[00:33:33] Speaker B: You're listening to Sustainability now. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschitz. My guest today is emeritus professor Ken Konka from American University, who has just published a book called after the Flood.

After the Floods, excuse me, which is focused on a place called Ellicott City, which I have been systematically mispronouncing in the first half of this show, But I won't do that again.

And we were just talking about why he decided to do, you know, do research in this particular space.

And, Ken, this is a participant observation, observer project, which is sort of uncommon amongst the academics that we. We've. We've palled around with.

And did this require you to sort of develop new methods of doing research? I mean, how did you go about doing this?

[00:34:34] Speaker C: Yeah, so that's a great question. And the quick answer is yes and yes and yes, as we've discussed. You know, I've been doing this for a long time. I've been a university professor and a researcher for 35 years.

I've been working on water for 30 of those 35 years or so.

I always had an international orientation because that's just always been my concern. And once I Woke up one day and realized, hey, water flows across borders. The obvious borders to study were the borders between countries.

I later learned that communities are bordered. Communities are bounded. Identities are bordered, Identities are bounded. And so there's lots of ways that once we take an expansive notion of what we mean by a border, where water flows across all of them.

I mean, it's even worse than that. If you think about how often rivers are used as borders in the sort of the modern template of carving out jurisdictions. Rivers are not borders, right? Rivers are arteries. Rivers should flow through the middle of communities. I grew up in Providence, Rhode island, which has a fabulous little river that flows right through it. And I never knew as a child, because it had mostly been paved over and rendered invisible and so on. If you've ever been to Providence, it's really nice today, the way since the river's been daylighted, it moves through the center, you know, the center of the community.

So my instincts were drawn to looking at these border crossing kinds of phenomena. And as a result, I always worked internationally. So I've done a lot of work in the corridors of the un I've done a lot of work around the World Bank. I've looked at the large dam controversies where the sort of the global political economy of creating these sacrificial landscapes around big hydropower, you know, is a thoroughly transnationalized and internationalized kind of process.

The deeper I got into it, the more I realized that I needed to be doing kind of multi level research and I needed to be doing very localized research.

So, you know, I've also done a fair bit of. Spent a fair bit of time standing in farmers fields and talking with them about rainfall and other sorts of things. You know, I've done that on probably five continents.

Never did anything in the United States, never did anything local. And so the fact that I was coming around to this was a real challenge. The other big challenge was that I was from Ellicott City, but I'm not of Ellicott City.

And the identities here were such a key piece, and I talk a lot about this in the book, that the real question was, what is it about this community that needs to be protected?

What do we have to save? And who gets to speak for this community to decide what to save and how to save it?

And that's fundamentally a question of political community and a question of identity. Right?

And because I lived on the other side of Route 29, which will be a very clear marker to anybody who knows the area, even though I was only four miles away, Even though I could ride my bike down Main street through the West End, where a lot of the damage in the community occurred, and even though my mail was addressed to Ellicott City, and even though a Google search, a Google map search would, would put me in Ellicott City, and even though the Census Bureau would tell you that Ellicott City is a. Is a community of maybe 60,000 people, including where I lived until just a few years ago, the heart of Ellicott City, the historic district of Ellicott City, the Main street community aspect of Ellicott City.

I was often seen as an interloper. Oh, you live west of 29, right? You're not from Old Town, that sort of thing. And so that was a challenge as well.

And another piece of the challenge.

Two other pieces of the challenge I'll mention just quickly. One was just the sheer volume of material. I spent hundreds of hours either sitting in meetings. I went to one meeting of the Historic Preservation Commission and, you know, people who own property, historic houses along Main street or in the, in the. It's an entire district that's listed in the National Register of Historic Places, which is unusual. Usually it's individual buildings here there's 28 buildings and there's an entire sort of, you know, square mile area that's listed in the, in the, in the register. And if you own property there, you can't paint the color of your shutters without getting permission from the Historic Preservation Commission. I went to a meeting in Historic Preservation Commission because I needed to understand how they played a role. I was the only person in the room who didn't have a case before the commission or grievance against the person who had a case before the commission. I remember the chair, every time he would ask, does anyone else have anything to say? And he'd stare right at me, trying to understand why I was in the room.

So I spent hundreds of hours in meetings, and many of these had this sort of small town feel. 100 people in a, in a high school gymnasium or a church basement or something like that, you know, pouring over maps and talking about pervious pavement and should we allow cars to park on Main street when the floods turned them into projectiles and all of that. So the sheer volume. I did 60 interviews for this book. I could have done 150 if I had the time. And, you know, with politicians and residents, shopkeepers, activists, etc. And that was very challenging. It took me six years to.

To write this book.

And the last piece of it is the Trauma.

There were People who wouldn't talk to me. And I totally understood why they wouldn't because they just.

They didn't want to judge it up again. They didn't want to deal with it. I had one person tell me that after the second flood in 2018, the second of the Sandwich of 2016 and 2018, that the book is centered on. Of course, there were many more previously after that flood, they were obsessively going to the web page where one local small business owner had set up a series of a dozen cameras to monitor the stream beds and Main street and various other other sort of key points in the community. And the experience had been so searing for them that afterwards they just had to keep the cameras on their screen all the time. And they had to look at it several times a day and just assure themselves. One local resident that I interviewed who owned a historic home in the area, and that doesn't. I promised anonymity to everyone and I don't quote them in the book because this was traumatic for many people and also because it was quite contentious and I wanted people to be comfortable to talk.

One person I interviewed, we were in a small coffee shop down on Main street, right where the worst of the damage had occurred.

And it was about 4 o' clock in the afternoon and the sky started clouding over me. She said, I gotta leave. I just can't be down here when the sun's not out.

It's just. I can't do it.

So it was an adaptive challenge for me to kind of fit into this space.

Social scientists get good at listening and interviewing and spend a lot of time doing that. So I was pretty comfortable with those modes of work, but to do it in my own community.

But was it really my own community or was I an interloper to do it with people who had suffered this sort of trauma and to have to have the patience to just watch all the complicated machinery of government. Department of Planning and Zoning, Department of Public Works, Historic Preservation Commission, five member county council, you know, et cetera, et cetera, grind their gears around this problem.

It was great fun. It was really interesting challenge and hopefully I produced an interesting book in the wake of it.

[00:42:32] Speaker B: Yeah, no, I think it's. It's quite interesting, particularly the. The question of, you know, why. Why don't things work? You know, why is it so difficult to come to some sort of agreement? I mean, we, we tend to think of these as more as technical problems. Right. You mentioned the tunnel, you know, which is, which is in the book. It's. It's a technical solution.

Okay.

Before we, you know, pursue that, I wanted to bring up the issue of property, which, you know, you've mentioned before. And property is obviously very important. I used Adobe Acrobat to count how many times you use the word. I came up with 113.

And it's always, you know, essential planning. What you've mentioned is that property is sort of understood in at least two senses in this story. One is in that historic sense, right. Relative to identity, that I own a historic building which, you know, has to be restored. And the other one, of course, is in terms of value of assets.

And, you know, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about, about how property plays out in these politics, in these, these sort of, you know, reconstruction efforts and planning efforts.

[00:43:56] Speaker C: For sure. I confess I did do a search on how many times I used particular words that comes out to about once every other page, although I'm sure some of them are bundled together. Right. But, but, but that's not inappropriate because it's a key, it's a, it's a key piece of the story.

I guess I would say two or three different lenses on how property became part of the story.

The first, and we'll probably circle back to this at some point, is larger forces outside the community had a lot to say about the ultimate direction that the responses went. And one of the, I'm reluctant to call it a tragedy. The county's done some good things. I do think people today are at lower risk than they were on that night in 2016 when the first of the two floods that I talk about hit.

There's been some progress made for sure.

But one of the reasons why I consider this to be a cautionary tale is that the divisions within the community around some of these questions around voice and participation and identity and et cetera, really left it more vulnerable than it otherwise might have been to some of these larger outside pressures. Some of those pressures were just sort of the churning of real estate markets in early 21st century American capitalism that saw an opportunity and what passes for urban renewal in America today, which is largely making an attractive space for tourists and, and high, well heeled visitors, high end visitors come and, and spend some money and, and, and, and so they're, you know, part of the process repeatedly had to deal with, with some people's idea of what a historically preserved mill town ought to look like when it's in this strategic place, you know, with 5 million people within an hour and a half drive away who can be walking up and down Main street carrying shopping bags. Right. And so that was part of the story. It wasn't the whole story.

You know, liberal problem solving, making this space a national model for flood resilience, et cetera, also had a lot to do with some of the solutions that were implemented. And what this more sort of, you know, conservative, capitalistic. This is an instance of property and investment opportunities and a more liberal. This is an instance of, you know, master planning to get it right and be a model for the rest of the nation. What those two things had in common is they never saw the place as a real place, as a three dimensional place, you know, with, with a lot of particularity to it. And that was some of the, you know, the violence, if you will, that I think has been done in the crafting of solutions. So that's, that's front and center as kind of like a big response. A couple of specific manifestations. Public versus private is an important part of the story here. And essentially there's public, you know, the county and almost everybody involved in this story understood the space as to be starkly divided between public property and private property property. And each of them was kind of subjected to only half of what is required for flood resilience in this space. So private property was subjected to increasingly tight regulations about managing runoff. And so you build housing now, you have to put in enough retention capacity for, for a certain level of flooding and, and so on. In the old days, it was just, you just had to have a gutter, you know, you had a pipe and pipe to the gutter and you could build. And that's been, you know, there's an increasingly tight regulatory regime that's created, but only applies to private property. It doesn't apply to public property. So there's an enormous courthouse complex, there's an enormous parking lot around that courthouse complex for some of the road building that's been done. I mean, you know, the county might say that it complies, or the state, because some of it is state level, road building might say that it complies. But all you have to do is look at the water coming off those roads in any significant rainstorm to know that it's not complying with the drainage regulations. So private property has to respond to the regulations, but it is sacrosanct and cannot be used to build any of the infrastructure. Right. The county made it clear on day one, we're not using eminent domain, we're not condemning anything, we're not imposing anything. And so a lot of the infrastructure that was built got crammed into public spaces because that was the only place the county was willing to build it, even if it was not an optimal place in which to construct.

So the private property is subjected to the regulatory regime, but is exempted from any need to be an actually resilient landscape and to have the infrastructure of a resilient landscape. The public property is forced to absorb all of the resilient infrastructure, but is not held strictly accountable for the regulations to manage runoff.

So this stark distinction between what is public and what is private is part of the problem.

And one of the things that I talk about in the last chapter, I mean, we'll probably get to this at some point. Last chapter of the book is, you know, you got to rethink public and private, and you got to be open to treating both of those as just, you know, holistic parts of the landscape. And then the other piece of this is housing. Right. One of the. And certainly development in the hills above the town is a big part of the problem. How big?

Some people want to talk about climate change because they don't want to stop development.

Some people want to talk about development because they don't want to talk about climate change. But it's clear that development's a big. To me and I think to most, and to the modeling, the development is a significant piece of the problem.

But most of that housing is what passes for affordable housing in Howard County.

Teachers, police officers, firefighters, they can't afford to live in this affluent county anymore. Half of the county is under conservation easements, so you're not building there.

Forget about infill. You can try to do infill. The county's official strategy is to do infill, which means, you know, adding development, you know, increasing density in existing mature neighborhoods. But those are the politically powerful neighborhoods, and they know how to fight off infill, if they know anything.

And so is this a smart place to be building affordable housing?

No.

Does the county desperately need affordable housing?

Yes. Is this one of the last places where it can be built? Unless you rework a lot of other things, yes.

So that's another way in which property becomes part of the conundrum. It's one of the central themes of the book.

[00:50:48] Speaker B: You're listening to Sustainability now. I'm your host, Ronnie Lipschitz. My guest today is Professor Ken Kanka, who was just published after the Floods, the Search for Resilience in Ellicott City, which is a small town in Maryland. And we've been talking about property. Ken, we're starting to get toward the end of our time together.

And I have a bunch of questions that I still wanted to ask. But let me ask you, what kind of broad conclusions about managing flood risk and planning and resiliency do you draw from the case of Ellicott City? I think, you know, what can we learn for other places where these kinds of things have happened and where, you know, planning's going on?

[00:51:39] Speaker C: For sure.

So the core message of the book is coming soon to a small town near you, or perhaps to your own small town, this vexing problem, right? And it might be around fires, California. It might be around fires, it might be around flooding, it might be around drought, it might be about coastal storms, but you're going to have to navigate it. And this town, with every seeming advantage, really struggled. So what lessons can we learn from this town?

And what I tried to do in the book was draw out a few big lessons that I thought were kind of running through the story, the book.

It's trying to be a readable book. It's organized as a chronological tale. So the chapters have title like before the first flood, the first Flood, after the first Flood, the second Flood, after the second Flood.

And part of that was because that's the way the community experienced it, right? What was known often didn't become clear immediately or got changed. And so I tried to give a sense of both how I was coming to understand the story as a participant, and also how people in the community and in government and in the Department of Public Works and Department of Planning and Zoning were coming to understand it. So it's organized that way. But there are three big themes that run through the verse, through the book. The first is about technical controversies, complexity, the politics of expertise.

And the county spent a lot of money on a fancy three dimensional model of the watershed. There was a very valuable tool. I learned a lot, I'm sure county officials learned a lot about how water behaved dynamically in the watershed. And it allowed you to say, what if we build an underground pipe farm here? What if we put a storage pond here? What if we improve conveyance instead of this 90 degree right angle that the stream channel is currently forced to undertake? How will that help under different storm scenarios?

But the problem with this is that the county tried, I would say tried to impose a certain expert based understanding of what the problem was on a community that wasn't having it and on a problem that reeked of uncertainty. And so the way I say it in the book, there's a lot devoted to this question in the book. But the Way I say it in the book is that the use of this model, helpful though it was, gradually changed. The question from a starting question of how can we enhance flood resilience in the watershed to what ended up fairly quickly being the question, how can we reduce the peak depth of water on Main street during very large flooding episodes by building big, but not too big infrastructure as long as it can be cited on public land while not talking about land use, climate change, or using the power of public domain?

And there's a very, and I try to describe this in the book, there's a very subtle process by which the way the model output became sort of like the myth and ceremony of this process. It became the sort of the religious faith that couldn't be questioned of this process when there were tremendous ambiguities in the modeling. And the modelers would be the first to acknowledge that. I thought they did a pretty good job of presenting it to the community and explaining what you could and couldn't infer from the results. But they took on a sort of a life of their own, and they really, really narrowed the imagination of the county and the community about how to respond to that. So this, this, you know, how whose knowledge counts, whose expertise is embedded in that model, whose local experiential expertise is excluded? That's one of the themes of the book. Second theme is around participation.

It was a very narrow group of people that came to the front. It was predominantly older, white crowd. These people had a deep stake in historic houses or in commerce around Main Street. But in a county of a highly Diverse county of 350,000 people, there's no way that the deep engagement of a few hundred people was going to create the kind of legitimacy that was required. And so how do you have a legitimate conversation about this and who gets to speak is the second theme of the book. And the third theme is about identity.

[00:56:09] Speaker A: People.

[00:56:09] Speaker C: Everybody agreed Ellicott City was special and had kind of a fierce sense of commitment to it. But the more you drilled into that, the more I sat with people. And one of my interview questions was my first question, what makes Ellicott City special?

And they'd always go to the history, you know, other things, the charm, the easy quality of life. It's not modern suburban malling of America. It's quaint, it's old. But it was always the historic identity of the town that would come out as one of the key pieces that made it special. But for some people, that was really grounded in the buildings. For some people, it was grounded in the idea that you had 300 years of continuous commerce in this space. You know, there's a. There's a mill looking over the river. It's the last of the old big mills.

And to some people, that structure is. Is almost like a cathedral. Other people will be quick to point out that for half of its life, that mill was a donut factory that employed predominantly African American laborers. In fact, after World War I, they promised anybody who came back from the war could have a job at the donut factory if they needed one. Right. And so it's not that the place wasn't special, but the community became very, very divided around questions of is it the structure?

Is it the concatenation of all of the structures, Is it the social identity of the place, Is it the ecology of the place? And because there had not been a systematic process of coming to an understanding around that, and suddenly there's the pressure of acting very quickly, quickly in time, these questions became very divisive, and that left the community vulnerable to some of these broader churning forces that I was describing earlier.

So I think this question of the politics of expertise, what knowledge is relevant and whose knowledge counts? This question of how do we have an equitable and democratic conversation about these, particularly in the current sort of. Of communications and polarized space we live in, and how do we have an ongoing conversation about what it is that this community means to us and what is most important for us to protect and preserve and cherish those. That's what it was really about. It wasn't really about flooding.

[00:58:30] Speaker B: Well, Ken, we're. We're out of time, but this has really been an interesting conversation.

We could spend a lot more time on it, I think. But thank you so much for being my guest on Sustainability Now.

[00:58:43] Speaker C: Absolutely. My pleasure, Ronnie. Thank you.

[00:58:47] Speaker B: You've been listening to Sustainability now interview with Ken Kanka, professor emeritus at American University in Washington, D.C. who has just published after the Floods the Search for Resilience in Ellicott City, a study that offers a blow by blow account of struggles and over rebuilding and elucidates his explanation for why they arise and persist long after the water has vanished. If you'd like to listen to previous shows, you can find them@case good.org sustainability now and Spotify, YouTube and Pocket Cast, among other podcast sites.

So thanks for listening and thanks to all the staff and volunteers who make K Squid your community radio station, and keep it going.

And so, until next, every other Sunday, Sustainability Now.

[00:59:41] Speaker A: Good planets are hard to find out Temperate zones and tropic climbs and natural currents and thriving seas.

Winds blowing through breathing trees.

Strong O zone and safe sunshine.

Good planets are hard to find. Yeah.